1. Introduction

Inundations are caused by random natural phenomena (river overflows, snow melting and rain, groundwater table rising above the terrain level due to infiltration, marine storms, and volcanic eruptions), accidents (dam or dike damages, wrong or faulty handling of spillways and bottom outlet facilities of dams during floods, and the sudden sliding of the mountainsides into a reservoir), or human activities (excessive or rapid filling/emptying of reservoirs and improper drainage of irrigation systems).

Due to its specific climate, Romania is frequently impacted by inundations, mainly provoked by floods occurring on rivers. They usually occur during spring due to snow melting and heavy rains. However, they may occur also in summertime due to severe storms. Over a period of 30 years at the end of the 20th century, Romania faced three catastrophic inundations, in 1970, 1975, and 1991, and smaller ones in 1983 and 1988, leading to a loss of human life and important socio-economic damages (estimated to be about RON 10 billion/year in the currency of that period) [

1]. Therefore, an extensive flood defense system was built, which proved its capacity to prevent, avoid, limit, or mitigate the impact of extreme hydrologic events that occurred after its construction. One of the main Romanian rivers with a high flood risk is Buzău [

2].

In the context of climate change [

3], particularly in regions exposed to intensified extreme weather events and more recurring storms, the values of the design floods for which different types of flood control facilities were built are frequently exceeded. In this regard, researchers recommend considering a so-called climate change factor to modify design floods and adopting a continual review of flood risk management strategies based on updated information [

4,

5,

6]. For the existing flood defense facilities, increased runoff volumes can trigger the risk of their failure, with severe consequences for property and human life. Since the inundated areas can cover various types of land uses, in certain cases, flooding can also release significant volumes of undesired harmful pollutants [

4,

7,

8,

9].

The worst consequences, including loss of human lives, are caused by dam failures. Catastrophic examples of dam break accidents include the Malpasset arch dam in France (1959) [

10]; the Vajont double-curved, thin-arch dam in Italy (1963) [

11]; the Teton earthen dam in United States (1976) [

12]; the Belci earthen dam in Romania (1991) [

1]; the Gouhou concrete-faced rockfill dam in China (1993) [

13]; and the 14 de Julho dam in Brasil (2024), built using roller-compacted concrete [

14].

A study conducted by Costa (1985) [

15] indicates that about 34% of dam failures are due to overtopping, 30% are due to foundation defects, and 28% are due to internal erosion (piping). Furthermore, the likelihood of overtopping failures will potentially rise given climate change trends that will bring about significant variability in precipitation patterns.

Adamo et al. (2020) indicate that about 77% of all built dams at the global level are embankment dams, of which 13% are rockfill dams and 64% are earth fill dams [

16]. Their failure is strongly influenced by the materials and configuration of the structure, acting forces, and different environmental causes [

17]. Understanding the failure mechanism and breach processes of this earthen dam category is of significant relevance to setting up realistic scenarios for developing numerical models.

Hydraulic models that simulate the catastrophic consequences of dam break accidents are indispensable tools to assess the time and space evolution of the inundation caused by the flood wave released through the breach, useful outputs for further development of risk management, and mitigation measures for such disastrous events [

18,

19]. Various numerical modeling packages are used for this type of simulation, such as TUFLOW FV, Mike 21, Telemac 2D, Delft3D Flow, SOBEK 2DFLOW, InfoWorks 2DHEC-RAS 5 and 6, LISFLOOD-FP 8.0, and DIVAST-TVD.

Most of them use 2D approximation to integrate shallow water equations (SWEs) through either finite difference or finite volume numerical methods. These equations include a mass conservation equation and two depth-averaged momentum equations to describe water flowing from one computation cell to another and compute the local values of depth and the averaged velocity components along the two horizontal directions [

20].

Numerical models developed to study the problems associated with dam break accidents have recently demonstrated notable advances in the field. Based on diverse complex computational techniques, such models are used to mimic the dynamics of dam failures, to analyze the progression of the flood wave released following the breach of the dam, to evaluate flood hazards and risks, and to assess sediment transport. These developments contributed to deepening the understanding of the hydrodynamics of such phenomena that occur in various circumstances. Maranzoni and Tomirotti [

21] presented studies using 3D models to simulate flood wave rooting over irregular topography. The benefits and limitations of the three-dimensional models compared to the two-dimensional depth-averaged approaches are emphasized using case studies for their validation [

21]. Aureli et al. [

22] give a comprehensive review of dam failure accidents benefiting from existing data sets, stressing the use of numerical models validated against real-field data. Furthermore, the article also presents studies exploring dam break flood routing using physical models designed to replicate actual topographies. Issakhov et al. [

23] developed a 3D model to evaluate dam break flows over fixed and movable beds. To simulate the movement of the free surface of water and mud, the authors combined Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluid models, whereas the solid macroscopic particles’ movement was performed using the discrete phase and macroscopic particle models. These features facilitate the enhancement of existing models to approach real dam break problems. Federico and Cesali, C. [

24] studied the impacts of the hypothetical failure of the Sciaguana embankment in Sicily on downstream flood routing, considering piping and overtopping breaching mechanisms and using the 2D unsteady flow simulation in HEC RAS. The paper highlights the importance that inundation maps have for dealing with risks and mitigating the consequences of a dam failure. As well, Mattas et al. [

25] assessed the flood hazard of the potential Papadia dam break in Greece using the HEC-RAS 2D capability. The computations were run in two failure scenarios, namely, overtopping and piping, and were carried out by varying the mesh size and breach parameters to evaluate their influence on the results of the model [

25].

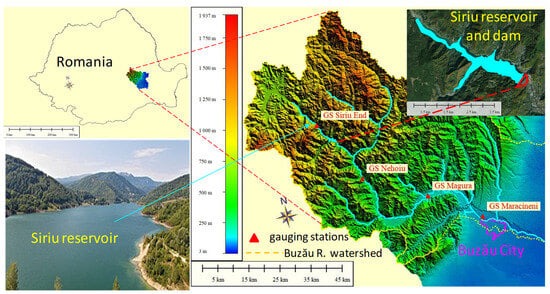

When it was commissioned in 1994, the Siriu Dam on the Buzău River in Romania was the second largest embankment dam in Romania and the fifth of this kind in Europe. The Siriu embankment dam has rockfill materials and a clay core and is ranked in first class of importance and category B of risk, according to the Romanian legislation in the field [

26,

27]. Given its rank, design particularities, and scale, as well as location, the present study aims to provide a valuable analysis of the consequences of such undesirable accidents.

The research involves numerical simulations using a 2D hydraulic model in HEC-RAS. An analysis of flood wave routing, considering multiple cases of hypothetical dam failure of the Siriu Dam, is made. Chosen scenarios consider extreme precipitation events and failure modes (overtopping and piping). For each case, the study provides as results the following hazard parameters, in locations of interest, necessary to assess the impact on downstream life and property: depth, velocity, and flooded area.

Most numerical studies for clay-core dam breach cases either deal with the mechanics of the failure [

28] or compute the depth and velocity maps downstream the dam to quantify the flood hazard [

29]. Unlike those, the present study adds as an important contribution the analyses of the flood routing and the dam break wave characteristics (the travel time, travel velocity, flooded width, maximum velocities and depths, and depth × velocity) as functions of the scenario parameters and specific site features, such as the terrain topography, river channel width, built dikes, and hydropower facilities. Another new aspect is that simulation scenarios take into consideration a time breach progression curve based on the failure mechanism for this clay core type of embankment dam. To quantify the hazard useful in the development of risk maps and flood management plans, a new depth

× velocity product is proposed to be used in Romania, instead of simply either the depth or velocity, as currently used. And lastly, a flood hazard analysis for this type of accident has not been published so far for this important dam.

The obtained results of the hazard parameters are prerequisites for developing flood risk maps and appropriate measures to mitigate the impact of such a catastrophic event [

30].

3. Results

Knowledge of all the flood characteristic parameters, such as local discharge, depth, velocity, travel time, flooded area, wave travel velocity, residence time, etc., are critical for the development of flood emergency plans, better preparedness, and mitigation measures that can reduce losses associated with such a disaster.

The results of the simulations showed the dam broke after 13 h for scenario S1 and 14:20 h for scenario S2, since the beginning of the incoming flood. It must be noted that for both scenarios, the peak discharge of the inflow hydrographs occurs at 16:00 h from the beginning of the formation of the breach. This means the breach occurs only 3 h before the reservoir inflow reaches its peak for scenario S1 and 1:40 h for scenario S2, respectively. For scenarios S3 and S4, the breach starts 2 h from the beginning of the simulations.

Computed parameters are investigated in eight cross-section profiles, delineated in

Figure 6, close to the inhabited locations shown in

Table 7.

The computed dam breach hydrograph and how it routes downstream the river valley is one of the most important results of the simulation (

Figure 9).

Upstream of Buzău City, corresponding to XS profile 7, the released flood wave reaches over 5 000 m3/s in all scenarios, indicating the exceedance of the design flow for the dikes (of 2440 m3/s, with a 0.5% exceedance probability) and, therefore, the flooding of the northern part of the city. Also, in XS 8 corresponding to downstream Buzău City, the maximum discharge is still over 5 000 m3/s in scenarios S1, S2, and S3. Compared to scenario S4, in these three cases, there are important additional water volumes in the reservoir that are released downstream at the breach start time.

The stage hydrographs upstream (US) of the dam show how the reservoir is filled and emptied over time, whereas the stage hydrographs downstream (DS) of the dam show the time evolution of water elevation in the section immediately DS of the dam (

Figure 10). The dam breaks 1:20 h sooner for scenario S1 compared to S2, even though the breach initiates at the same water elevation over the deck. This time lag can be attributed to the increased volume of water entering the reservoir for S1. Also, an increased water surface elevation downstream the dam for S1 compared to S2 can be observed.

The travel time of the dam wave front is depicted in

Figure 11. These curves are very useful for developing the emergency action plans in the region. While the flood wave leaves the mountain area about 2 h after the dam break, it reaches the plain area in about 5 h and Buzău City within 6 to 7 h for all four scenarios. The travel time depends more on the incoming flow than on the initial reservoir elevation. In

Figure 11a, one may see that a difference in the incoming flow between 2440 and 1760 m

3/s for scenarios S1 and S2 leads to a difference of 0.5–1 h in terms of the front wave travel time in the specified locations. The lag time increases after the stream leaves the Subcarpathian region, and the floodplain enlarges. This is due to the increased inertia component of the acceleration (terms B in momentum Equation (2)).

Figure 11b (for piping scenarios S3 and S4) shows that 9 m more of initial water surface elevation in the reservoir leads to the flood wave arriving 1h sooner 80 km downstream of the dam. In Buzău City, the difference is also 1 h.

Figure 12 shows that the front wave travel velocity increases along the Carpathians region, reaching maximum values (between 12 and 14 m/s) in the Subcarpathians, followed by a slight decrease at the entrance in the plain zone. The trends depicted by the wave travel velocity are similar for both scenarios S1 and S2, with higher velocities of about 2 km/h for scenario S1 than for scenario S2 (

Figure 12a). This is obviously due to the additional water volume released from the dam in the case of S1.

Likewise, for the piping scenarios S3 and S4, the wave travel velocities follow the same variation pattern downstream the dam as in the overtopping scenarios (

Figure 12b). However, they are marked by lower values than in S1 and S2, and the difference between the wave travel velocities decreases, on average, at about 1 km/h. Since the flow velocity depends on the product of hydraulic radius and energy slope and their individual trend along the river is to increase and decrease, respectively, this might explain the plateau of the velocity along the middle reach.

By displaying the maximum velocity over the entire simulation period in each grid cell for different cross sections along the river (

Figure 13), one may see that these velocity values drop from 15 to below 5 m/s, where the sinuous stream leaves the mountain region, and it begins to develop its braiding/wandering planform pattern [

47]. Also, the shape of the maximum velocity profile plots in XS1 and XS4 (details in

Figure 13) show the stream flows only through a main channel along its Carpathian course. Then, 65 km from Siriu dam, where the valley enlarges into a floodplain, there is another small dam with a narrow reservoir (Cândești), upstream/downstream of which the water flows in parallel through both the hydropower plant feeder/tailrace canals and the natural river channel, as the velocity profile shapes from XS6 and XS7 show (

Figure 13).

The plots of the maximum depth and velocity (over the simulation time) along the thalweg line and in each of the eight study cross-sections (

Figure 14a,b) show a similar decreasing trend for all four scenarios.

Maximum depths are very high along the first 20 km from the dam (in the mountain region, where the Buzău River Valley is narrow), in the range of 15–25 m. They drop to values below 10 m at distances over 20 km.

Maximum velocities drop similarly from huge values of 10–12 m/s to smaller values below 6 m/s as the river enters the plain region. While the decrease in depths with the distance from the dam is due to flood wave attenuation, the velocity reduction could be attributed to both attenuation and thalweg slope, as seen in the longitudinal profile of the river in

Figure 14c. This slope drops from 0.9% over the mountain reach to 0.3% over the Subcarpathians and to 0.17% over the plain reach, with an average value of 0.4% over the entire 100 km reach.

At the same time, the inundation boundary width in the studied cross-sections increases with the distance from the dam (

Figure 14c) from hundreds to thousands of meters, showing its largest value at the entrance in Buzău City (XS7, at 80 km from the dam). In this location, the current splits (due to the topography) and floods the Western and Southern part of the city at high discharge values, as in the case of scenarios S1 and S3.

An example of the inundation boundary for scenario S4 is presented in

Figure 15 with details of an inhabited area downstream Siriu dam (bottom-left corner) and of a flooded dike near Buzău City (top-right corner). Depths and velocities in the city from the corresponding hazard maps are under 1 m, and velocities are under 2 m/s.

The flooded areas of Buzău City were computed as a percentage of the total surface by intersecting the computed inundation boundaries in all four scenarios with the contour of the city in QGIS software version 3.10.9 (

Figure 16). One may see that the first two scenarios lead to similar flooding areas irrespective of the incoming flow, whereas a higher initial water elevation in the reservoir entails much greater damage (38% compared to 15% flooded area). However, this result does not take into consideration the water depth and velocity.

In

Figure 17a,b, example details of the depth x velocity map are shown in the North-East of Buzău City for scenarios S3 and S4 9 h after the initiation of the dam break. Values of the product (up to 20 m

2/s) are classified according to the proposed quantification method from

Table 6. One may see the highest values are in the river channel, and the choice of the scenario is a major factor of influence in terms of the potential flood damage. This hazard quantification method may be used in the future for the development of risk maps and flood emergency plans.

To see the inhabited area in the city affected by flooding, the results were exported to Google Earth (with the option of 3D buildings activated). Details of the computed water level with respect to building heights are shown in the bottom-left corner of

Figure 17 for the flooded Orizont district from Buzău City. This Google Earth facility might be very useful for educating citizens about the hazard of such an accidental flood.

4. Discussion

The findings of the study are marked by the specific location of the dam in terms of topography and the particular physical environment.

Table 8 summarizes the results of similar approaches to the present paper obtained by researchers who numerically investigated the impact of embankment dam break waves on downstream inhabited regions to provide an insight into the scale and severity of a possible disaster.

For all studies, the peak values of the maximum depths and velocities were found to occur within the few km downstream of the dam, mainly in highland reaches with steep longitudinal slopes.

Chen and Carpat [

54] compared their numerical results for the Teton earthen dam break wave characteristics, obtained for non-uniform valleys, with the surveyed ones. The water depth showed a similar decreasing trend to that in

Figure 14a), from about 29 m at the dam to 7 m at 100 km downstream of the dam for a peak dam break discharge of nearly 47,000 m

3/s.

Also, a peak value of 33,000 m

3/s, having the same order of magnitude as the peak discharges in

Figure 9, was obtained numerically by [

55] for the overtopping failure mode of the 116 m high Atasu rock fill-type dam in Turkey.

Doğan et al. [

56] developed a numerical model to study the possible failure of another dam with rockfill and clay core in Turkey, the Gökçe Dam (62 m in height), using different sets of breaching parameters. The peak outflows for the overtopping and piping scenarios were 12,000 and 6000 m

3/s, respectively. The results showed maximum velocities of 14.6 m/s and 22 m/s along the first 2 km downstream of the dam in these two scenarios, respectively, comparable to the ones for the Siriu Dam. For a mean longitudinal slope of the river of about 0.78%, the computed travel time of the flood wave along a reach length of 8 km was between 5 and 10 km/h. These values are in the same range as the ones obtained along the mountain area for the present study.

Researchers who published [

56,

57,

58] obtained larger peak flows for overtopping than for piping failure scenarios, like for the Siriu dam break. However, a paper studying the failure of the Sattarkhan dam [

59] did not provide any value for the outflow discharges. The only case that provided a piping peak discharge greater than the overtopping one is [

60].

The largest peak discharges were obtained by [

58] for the Hidkal Dam in India. Further comparisons of other dam break wave parameters are difficult to be made, since studies do not offer the same type of results. Also, the uniqueness of the sites and dam particularities make such a comparison even more challenging.

5. Conclusions

This study examines the consequences of a possible failure accident of the Siriu clay-core embankment dam from Romania. The selection of the case study was based on some important criteria, including its location in a region subject to earthquakes and high flood risk, dam type, and previous dam problems that determine the need to implement a safety surveillance program. Four hypothetical breach scenarios were chosen, two for overtopping and two for piping failure modes. The breach parameter values were calculated using empirical formulas developed previously by other authors.

The main objective of this study was to analyze flood wave routing and hazard characteristics in terms of chosen scenarios and site-specific features. To achieve this objective, a fully dynamic 2D hydraulic model was developed under HEC-RAS.

The computed results include details about the dam flood wave and its progression downstream, the stage hydrographs upstream and downstream of the dam, and the hazard characteristics. The last ones consist of depth, velocity, inundation boundary, and depth × velocity maps. As expected, water depths and the flow velocity decrease along the 100 km study river reach from 20–25 m and 15–20 m/s downstream the dam to about 3 m and 3 m/s, respectively, in Buzău City, while inundated width increases from several hundreds to several thousands of m, over the same distance. The simulated dam break flood wave reaches Buzău City in 7–8.5 h, depending on the scenario involved. The incoming flow and initial water level in the reservoir were proved to be the determining factors for the travel time, front wave velocity, and inundation depth. Details of the flooded area of the City of Buzău were provided as a function of the scenario. A new hazard quantification method for Romania was proposed based on the water depth and velocity product.

The accuracy of the findings is certainly influenced by different factors, such as the resolution and precision of the digital terrain model, the chosen Manning roughness parameters (since such models cannot be calibrated on previous data from similar events), and the selection of breach scenarios.

The results of the current study could contribute to the selection of optimal adaptation measures to be taken to limit the impact of such catastrophic dam break events to mitigate the flood risk, prepare inhabitants, and increase the resilience of the affected communities.