1. Introduction

Those in professions which require caring for others are united by their empathy and compassion for those who need it. These care professionals may include nurses, psychologists, veterinarians, and animal shelter workers, or informal caregivers, i.e., those who care for sick relatives or pets. These roles share similar demanding tasks, such as providing a consistent level of empathy for those that are suffering or unwell, and these demands can pose a risk to the health and wellbeing of care workers [

1,

2]. Declining wellbeing amongst those in caring roles also has repercussions for the recipients of their care, as they may face poorer outcomes as a result [

3].

Much existing research focuses on the mental impact of these demands in those who care for people [

4,

5], through concepts such as compassion fatigue in professionals and ‘caregiver burden’ in informal care workers. Compassion fatigue is conceptualised as an emotional state of exhaustion and diminished capacity to care [

6,

7,

8] as the result of empathetic exposure to the trauma of others [

9] and burnout caused by persistent high occupational stress [

10,

11,

12]. ‘Caregiver burden’ [

13] also explores how the time, physical, and emotional commitments involved in care provision can negatively impact the emotional and social functioning of those in informal caring roles [

14]. Naturally, however, these conditions and challenges are not exclusive to those who care for people, and there are clear indications that animal care workers also indicate stress in response to their work [

15,

16].

Animal care workers vary in their roles and responsibilities, with many being volunteers who may maintain another job, or are retired [

17]. These factors can make it challenging to determine who and how these workers are affected, as they may not have recorded employment, or their role may be filtered into different categories. Current research into the wellbeing of animal care workers has highlighted difficulties such as burnout [

18], grief [

19,

20], compassion fatigue [

21,

22], depression, and sleeplessness [

23,

24] to be prevalent in these roles. Further, veterinarians report a likelihood of suicide four times greater than the general population [

25,

26]. Studies that investigate the wellbeing of animal care workers often adopt concepts and strategies created for other caring professions out of necessity, such as compassion fatigue, and while this is important in determining the impact of caring work across disciplines, animal care workers take on a number of additional demands unique to their sector that may expand how they are impacted.

Animal care workers face several unique challenges, such as tending to injured and traumatised animals, comforting grieving owners, and euthanising animals they have had a role in caring for [

27,

28,

29]. Animal care workers in shelters and rescues are noted for their high empathy for animals and work in these roles to protect unwell and homeless animals [

30]. This moral motivation, in addition to their attachment to animals, can lead to their continued work, despite feelings of distress from their role [

31]. Further, it is also common for those in shelters or foster care positions to bring their work home with them [

31], reducing time for self-care and increasing attachment to potentially stressful situations. Accordingly, high occupational stress is reported by both shelter employees and volunteers [

21], such that one survey of 1000 shelter and animal-control workers by the Humane Society of the United States, reported in Figley and Roop [

6], found 56.4% of the sample self-reported as extremely high risk for compassion fatigue. Thus, shelter and rescue workers may be particularly susceptible to the challenges of animal care work.

Euthanasia exposure is often also assumed to play a unique role in diminishing animal care worker wellbeing, but research in this area is conflicting. Participation in euthanasia has been linked to poorer mental health in animal shelter workers by Baran et al. [

32] and Scotney et al. [

15]. Other studies, however, found that neither indirect nor direct exposure to euthanasia had a significant impact on wellbeing [

19,

33,

34]. Conflicting findings may be due to factors such as the relationship between the care worker and the animal [

35], the reason for euthanasia [

36], whether one morally agrees with the decision [

37], or whether they feel responsible for it [

19]. More research is needed to understand this variability relating to the impact of euthanasia in shelter and rescue workers.

Organisationally, poor wellbeing amongst animal care workers can increase intentions to leave their role or the field altogether [

38,

39,

40,

41], and this subsequent turnover is notably highest within a year of first exposure to animal euthanasia [

42,

43]. This can increase work pressure on remaining staff [

44] and interfere with organisational processes [

45].

It is clear that the mental health fallout of work stress is central in available animal care worker literature [

20]. While this research is vital in identifying areas which can be targeted in wellbeing interventions, the interrelationships with other domains of health have been understudied in this population. Health is a complete sense of wellbeing across physical, mental, and social factors [

46]. The limited research on other health domains is despite findings that link burnout with physical fatigue and pain in other contexts such as teaching, social work, and nursing [

47], as well as increased physiological indicators such as blood pressure and heart rate being linked with the high stress in animal shelter and veterinary roles [

19,

34]. Reeve et al. [

42] also highlighted how poor physical wellbeing in animal care workers may occupy greater organisational resources. Additional research which adopts a wholistic view of health, and its contributing factors, in this subset of workers is required.

A potential way to conceptualise the relationship between health and occupational factors in animal care workers is through the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) framework [

48]. This framework identifies all aspects of a job as either demands or resources. Job demands are those with a physical, psychological, social, cognitive, or emotional cost to the worker [

48], and within the model include work pressure and emotional and cognitive demands [

49]. Job resources aid in the completion of work, reduce work demands, or promote growth [

48]. Some examples include social support, feedback, and autonomy [

49]. Resources have been linked with improved wellbeing, improved job satisfaction, and lower turnover [

50]. Some challenges animal care workers face that contribute to demands within the model, include: grief [

20]; workload or job insecurity [

51]; and, although unique, animal euthanasia exposure [

15]. Social and organisational support [

40,

52] and empathy for animals [

20,

53] are considered notable resources. When resources cannot mitigate demands, continued work may pose a risk to the health of care workers.

Monaghan et al. [

33] utilised the JD-R to examine wellbeing in employees and volunteer animal rescue and shelter facilities, finding that significant traumatic stress and burnout variance was explained by job demands, but job resources did not moderate this relationship, contrary to expected JD-R relationships [

50]. Instead of moderation, studies examining the capability of resources in directly predicting wellbeing in veterinarians and shelter workers provide better support for the JD-R in this context [

40,

54], although the impact of different resources varies across studies. One study by Paul et al. [

20] examined how JD-R factors predict wellbeing in animal care workers, finding that both the severity of their grief experience and perception of organisational support were significant, opposing predictors of burnout. The authors’ qualitative findings suggested further research exploring organisational resources is necessary, as participants’ wellbeing concerns arose from factors predominantly under organisational control.

Organisational justice (OJ) presents one resource that may be important to animal care workers in shelters and rescues. OJ represents an employee’s perception of fairness within an organisation, split across four justice dimensions: distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational [

55,

56]. These dimensions refer to the degree to which employees perceive outcomes are a fair reflection of their input (i.e., distributive), that workplace procedures are fair and consistent (i.e., procedural), that they are treated respectfully by authority (i.e., interpersonal), and their belief that there have been adequate communications from superiors (i.e., informational) [

55,

56]. High OJ perceptions in healthcare have predicted better work engagement, better wellbeing, and lower turnover [

57,

58], whereas lower OJ perception in non-healthcare work environments has been linked with psychological distress [

59], poor self-rated health [

60], and higher risk of sickness-related absence [

61]. Not yet examined in this population, there is partial support for the notion that OJ is important for animal care workers as studies of similar concepts such as ‘voice’ [

17], job control [

52], and decision-latitude [

23] found that these play a role in their satisfaction and wellbeing. If this is the case, further research specifically exploring the role of OJ in this population is necessary.

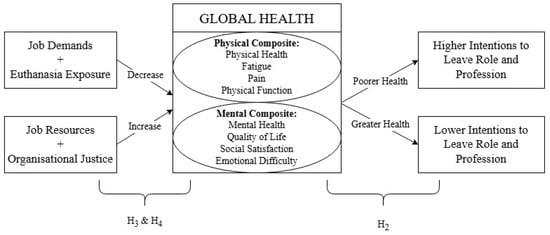

The health of animal care workers in shelters, rescues, and management facilities (e.g., municipal pounds) may be more broadly affected by their work than current literature indicates, as elements of health, such as physical health, have not been explored to the same extent as mental wellbeing, despite evidence suggesting they may be affected. It would be instructive to examine wider health factors in these animal care workers and explore contributing factors using the JD-R, including the role of OJ. As such, this study aimed to explore global health among those working in animal management, sheltering, and rescue, as well as to assess whether this is associated with turnover from work, job demands and resources, and OJ. First, it was hypothesised that participants would self-report lower than average physical and mental health (H

1). Second, self-reported health would be inversely correlated with turnover intention (H

2). Third, higher job demands would predict poorer self-reported health, whilst higher resources would predict greater health (H

3). Fourth, higher OJ perception would predict greater health (H

4). The explored relationships are shown in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was part of a larger collaborative project with PetRescue, a national charity that facilitates the adoption of pet animals, coordinating with other rescue organisations in Australia. Only survey items related to the present study aims are detailed.

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of La Trobe University (HEC24226). Individuals working within the sector were consulted during question design to ensure relevant topics were addressed and question wording was suitable and appropriate to those working across the sector. Participants were fully informed of the study aims and were provided with contact details of support services (i.e., Lifeline and Beyond Blue) to access should they experience discomfort and want to talk to someone. This information was presented in a Participant Information and Consent Form, and again at the beginning and towards the end of the survey.

2.1. Participants

A snowball sample of animal care workers was recruited between July and August 2024. It was required that participants were: currently residing in Australia; over the age of 18 years old; able to read and write in English, the language of the survey; and, working in a paid or volunteer role for an animal management, shelter, and/or rescue facility. A link containing recruitment, study, and consent information was distributed to animal shelters in the rescue directory of PetRescue via email, advertised on social media (i.e., Facebook, LinkedIn) through PetRescue and other state and national peak bodies, as well as shared within research groups. Participants were also asked to forward the study to relevant industry contacts. A total of 406 responses were recorded. Those who did not attempt the full battery of health and workplace measures were excluded, although demographic items were optional and full completion of these was not required for inclusion. The final sample included 285 participants with usable questionnaire completion. Participants ranged from 19 to 94 years of age (M = 49.8, SD = 15.6). The wide age range in the sample may be explained by the prevalence of volunteers within this industry, and thus it may have attracted those outside typical working age or circumstance (e.g., those that are retired from full-time work).

2.2. Measures

The present study utilised a cross-sectional survey design. Data collection was conducted using an online anonymous survey hosted on QuestionPro Survey Software [

62].

2.2.1. Demographics

Individual and organisation demographic factors were recorded using 9 items developed by the research team in consultation with industry members. Participants were asked for role and organisation information, in addition to their age and gender. Participants could select multiple roles as this is not uncommon in this field [

63]. It is notable that significantly fewer responses for the item relating to the participant’s gender identity were recorded. During consultation, it was indicated by some industry members that they felt queries of gender may not seem relevant to all respondents when answering a survey about health and their experiences in the industry. This, together with the item being optional and positioned near the conclusion of the survey, may explain the lower response numbers in comparison to other demographic items.

Table 1 details demographic characteristics for the final sample of animal management, shelter, and rescue workers that participated in the study.

2.2.2. Global Health

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System—Global Health v1.2 10-item scale (PROMIS-GH; [

64] measured self-reported global health, where every item considers a different domain of health [

65]. Six PROMIS-10 items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from poor to excellent health, one item addressing physical ability is scored from ‘not at all’ to ‘completely’, two items referring to emotional difficulties and fatigue are displayed negatively where higher values indicate worse health, and one item addresses level of pain on a 10-point scale from ‘no pain’ to ‘worst pain imaginable’ that is recoded during analysis to a 5-point response. Usage of the PROMIS-GH was in adherence with the Terms of Use for research publications outlined by HealthMeasures.

Four items comprise a physical health composite (PCS; i.e., health, functioning, pain, fatigue, e.g., “To what extent are you able to carry out your everyday physical activities such as walking, climbing stairs, carrying groceries, or moving a chair?”), and four items correspond to a mental health composite (MCS) that is inclusive of social factors (i.e., quality of life, mental health, social satisfaction, emotions, e.g., “In general, how would you rate your mental health, including your mood and your ability to think?”). Two individual items (i.e., general health and social functioning) are not used in the composites; however, they are highly correlated with PCS and MCS [

65].

Consistent with previous studies [

66,

67], only the composites were used for analysis as individual health items are not as precise [

68]. PCS and MCS were converted to t-scores included with the measure, with a mean of 50 and SD of 10 based on general population norms [

69]. Composite scores of the PROMIS-GH have good internal reliability (MCS, α = 0.88; PCS, α = 0.82) and support for convergent and divergent validity in previous research (Cella et al., 2010). PROMIS-GH is primarily used with inpatients, although it has previously been used to study the health of unpaid cancer caregivers [

67].

2.2.3. Intentions to Leave

Intentions to leave were measured with two items [

33,

54] rated on 5-point Likert scales from ‘not at all likely’ to ‘extremely likely’, asking participants to report their likelihood to leave their current role, and animal caregiving work entirely, within the next 12 months. Turnover intention is considered a reliable predictor of actual turnover [

70,

71].

2.2.4. Job Demands and Resources

The Job Demands-Resources Questionnaire (JD-RQ; [

49]) was used to measure job demands and resources. The present study included job demand scales of work pressure, cognitive demands, and emotional demands, as well as job resource scales of autonomy, social support, and feedback, totalling 20 items. Participants rated items on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘never’ to ‘very often’, or ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, where high scores correspond with high perceived demands or resources. Reliability and validity for subscales are not available in Bakker et al. [

49], but this scale has been widely used to measure job demands and resources, and it has been shown to be reliable (JD, α = 0.82; JR, α = 0.76) in previous, similar research [

27,

33].

2.2.5. Euthanasia Exposure

Euthanasia exposure was measured using two items [

33,

54] that assess direct (participation, e.g., “To what extent are you directly involved in the euthanasia of animals you care for (e.g., restraining the animal, injecting the solution)?”) and indirect (knowledge of events, witnessing, e.g., “To what extent do you have knowledge of animals you have cared for being euthanised, even when you do not participate directly in the procedure?”) exposure. Items were scored on 5-point Likert scales from ‘not at all’ to ‘completely’, where higher scores indicated greater exposure.

2.2.6. Organisational Justice

A shortened version of Colquitt’s [

55] 20-item, four-dimension organisational justice scale, reduced to eight items and three dimensions by Elovainio et al. [

72], was used to measure perceptions of OJ. The shortened scale was chosen to reduce the time participants needed to complete the full test battery. Items addressed procedural justice, distributive justice and interpersonal justice. The shortened scale excluded the informational justice dimension, as items overlapped with constructs captured more reliably by interpersonal justice items [

72]. Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘to a small extent’ to ‘to a large extent’, where higher scores indicated higher perceived OJ. Certain items require adjustment depending on the context in which the scale is used, e.g., “My [outcome] is appropriate for the work I complete” [

73]. Animal care workers may feel a number of benefits from their work, such as a sense of fulfilment, beyond how they are compensated or treated, and thus items were adjusted to allow for this interpretation, e.g., “The benefits I get from work are appropriate for the work I complete”. The shortened scale has good internal consistency, structural validity, and predictive validity [

72] and the original scale has been used to examine turnover amongst nurses [

58].

2.3. Procedure

The questionnaire, inclusive of items from the larger study, took an average of 29 min to complete. Participants read an information statement informing them of the questionnaire contents, that their responses after supplying consent would be recorded, and that they could withdraw from further responses at any time. Once participants selected ‘I agree, start questionnaire’, they were presented with demographic questions followed by the study measures.

2.4. Analyses

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0 [

74]. Frequencies and descriptives identified the sample, provided reliability of subscales, and evaluated the overall health levels reported, addressing H

1. Normality of dependent health variables was assessed through Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, as well as evaluation of histograms and box plots. Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistics for PCS and MCS were significant (

p < 0.001), suggesting a violation of the assumption of normality [

75]; however, the large sample size indicated parametric tests were still suitable for analysis [

76]. Pearson’s correlations were then calculated to test the relationships that MCS and PCS had with turnover intention, addressing H

2, in addition to euthanasia exposure, job demands, job resources, OJ, and age to examine zero-order relationships these predictors had with health outcomes.

To increase regression power, predictors were excluded if their correlation with health outcomes was non-significant [

77]. Hierarchical multiple regressions predicting each of MCS and PCS were then run. Assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity for each regression were examined using normal probability plots of the regression of standardised residuals, as well as scatterplots of standardised residuals against standardised predicted values. Correlation matrices and tolerance values were checked to assess multicollinearity amongst predictors. Multivariate outlier presence was assessed through Mahalanobis distances by comparing these to the critical value for the number of predictors in the regression, calculated using an alpha level of 0.001 [

78].

Age was entered at step 1 of the regressions to control for confounding effects on health. Direct and indirect euthanasia exposure were entered at step 2 to evaluate these separately from other demands. Job demands and job resources subscales were entered at step 3 to assess their relationship with health, addressing H3. Finally, perceptions of OJ dimensions were entered at step 4 to see whether this predicted additional variance in health, after controlling for other known factors, per H4.

5. Conclusions

The present study aimed to determine whether animal care work in management, sheltering, and rescue can impact global health by exploring how job-related factors such as demands and resources were related, including the role of organisational justice, using the JD-R model. Further, this study also aimed to explore the nature of any relationship between global health in this population, as well as intentions to leave one’s role or the industry altogether. Below average mental and physical health supported existing findings regarding mental wellbeing and added physical health as a new area of impact. Emotional demands, direct euthanasia exposure, and social support were revealed as significant predictors of mental and physical health alike, highlighting areas where these health domains are similarly impacted, as well as how physical health can be afflicted by intangible demands. Organisational justice was not predictive of health, but it was correlated.

The present study adopted a broader definition of health than just that which is linked to mental wellbeing, as has previously dominated research within this population and research area. Through this study it is apparent that elements of physical health may also be impacted in these roles, which may occur as a result of changes in mental health or may be affected independently and be in need of further research. Further, to the authors’ knowledge, this study was the first to examine organisational justice as a resource for animal care workers, although this requires additional inquiry from future research.

The findings of this study may suggest a lack of emphasis on health in the animal care industry, possibly due to either low awareness or inadequate knowledge of the ways in which health may be impacted by work-related stressors. Those in these fields should consider how the temporary and targeted wellbeing impact of high stress events may lead to more stable or broad health decline and take ongoing record of health to better identify point of decline to inform supports.

Future research would benefit from analysis of demands or resources uniquely related to physical health to explain if declines in this domain are isolated or a product of declines in mental health. Further, additional research is required to determine if organisational justice serves a moderating role between job demands and health outcomes.