Adapted from a release written by Michael Keller for ETH Zurich.

In brief

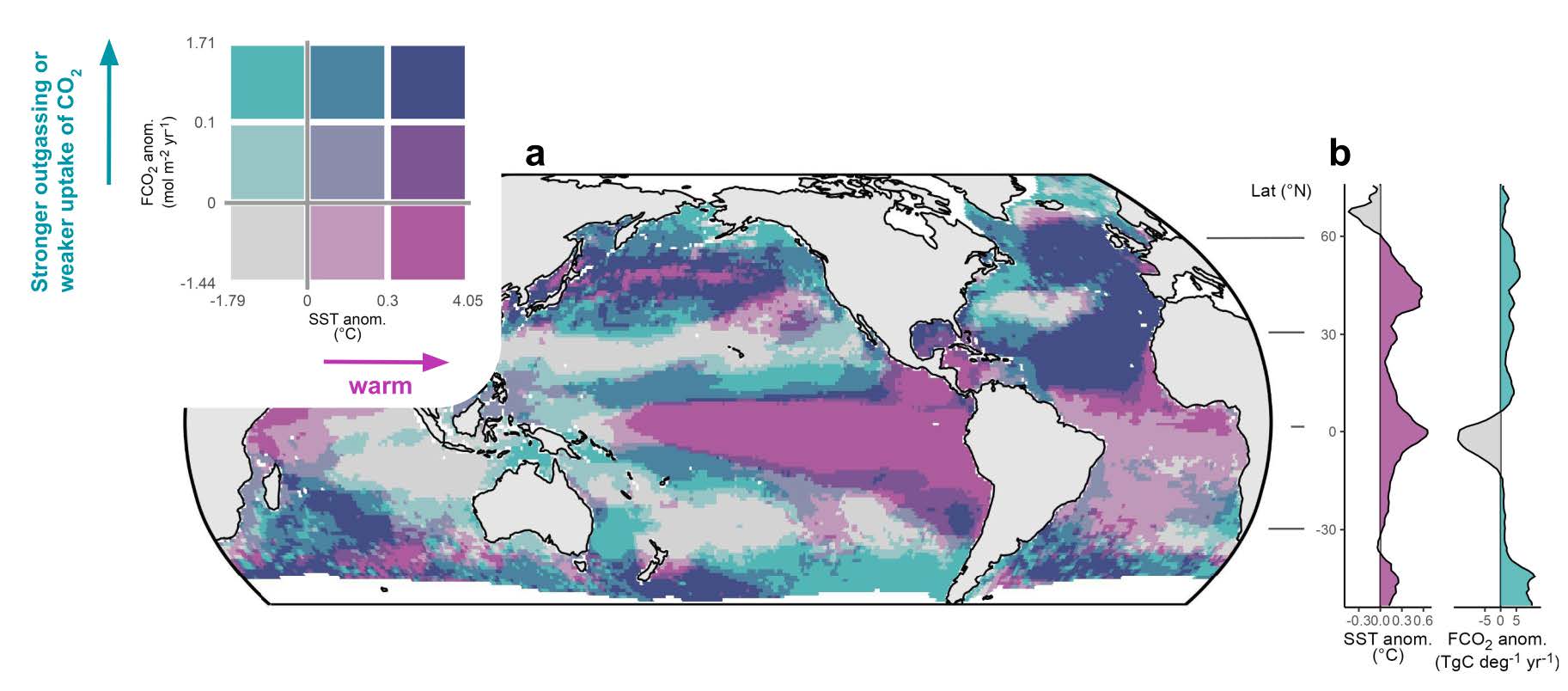

- Extreme sea surface temperatures in 2023 resulted in high CO₂ outgassing, particularly in the North Atlantic, meaning that the global ocean absorbed less CO₂ overall.

- Thanks to El Niño, much less CO₂ than usual escaped into the atmosphere in the eastern Pacific, but the outgassing in the North Atlantic negated the positive effect.

- The fact that the ocean did not lose even more CO₂ is due to physical and biological processes that limited outgassing despite the record-high temperatures.

- Researchers are unsure if these compensating processes will continue to effectively support the marine carbon sink as global warming progresses.

The world’s oceans act as an important sink for carbon dioxide (CO₂). To date, they have absorbed around a quarter of human-induced CO₂ emissions from the atmosphere, thereby stabilizing the global climate system. Without this sink, the CO₂ concentration in the atmosphere would be much higher and global warming would have already significantly exceeded the 1.5-degree warming limit set by the 2015 Paris Agreement. At the same time, the oceans absorb around 90% of the excess planetary heat that’s building up from global warming.

A new study published in Nature Climate Change reveals how the ocean’s carbon-absorbing capacity responded to the record-breaking temperatures of 2023. An international research team, led by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich), investigated for the first time whether and how the extreme ocean temperatures recorded two years ago impacted this crucial carbon sink, based on oceanic CO₂ measurements from a global observation network. The study is one of the first to draw on actual observations as a foundation for insights into the behavior of a warming ocean. The researchers relied on CO₂ observations from research vessels, cargo ships and buoys, combined with satellite data and machine learning to establish global maps of surface CO₂ levels. This enabled them to calculate the CO₂ fluxes between water and air at the sea surface.

Their results show that in 2023, the global oceans absorbed almost a billion tons, or around ten percent less CO₂, than anticipated based on previous years. This reduction is equivalent to about half of the E.U.’s total CO₂ emissions, or about a fifth of U.S. emissions.

“This reduction in the ocean’s CO₂ uptake is due to global warming, and it results in more CO₂ remaining in the atmosphere to promote even more warming,” says co-author Galen McKinley, professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences and senior scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, which is part of the Climate School.

In 2023, global sea-surface temperatures rose sharply, hitting record levels in various regions. The tropical Pacific was very warm due to a strong El Niño event. At the same time, weak winds in the North Atlantic kept surface waters warm by reducing the mixing of surface water with cooler water below.

“This sudden warming of the ocean to new record temperatures is challenging for climate research, because to date it was unclear how the marine carbon sink would respond,” says co-author Nicolas Gruber, from ETH Zurich.

Warm water dissolves less CO₂

The decline in CO₂ absorption wasn’t surprising to the researchers. “When a glass of carbonated water warms up in the sun, dissolved CO₂ escapes into the air as a gas, and the same phenomenon happens in the sea,” says ETH’s Jens Daniel Müller, the study’s lead author.

In 2023, high temperatures, especially in the North Atlantic, reduced CO₂ solubility and weakened the ocean’s carbon-absorbing capacity.

Whether the ocean absorbs or releases CO₂, however, doesn’t depend solely on temperature.

“If the only effect had been higher temperatures reducing CO₂ solubility, the cut to the 2023 ocean carbon sink would have been greater by a factor of 10,” says McKinley. “This reduction would have caused the global ocean carbon sink to collapse almost completely.”

But the study shows that the carbon sink decreased only moderately. This was mainly due to natural mechanisms in the ocean that reduce the concentration of dissolved carbon in the surface layers, counteracting the CO₂ outgassing promoted by warming.

Compensating forces stabilize the sink

The authors highlight three physical and biological processes that kept the amount of dissolved carbon low in waters near the surface of the ocean. The first is that the warmer waters caused CO₂ to bubble out of the surface layers. Secondly, the warm water acted like a lid that prevented CO₂-rich deeper waters from upwelling, thus maintaining the surface water’s ability to absorb more CO₂. And the third mechanism is a biological one: photosynthetic organisms in the warm, light-flooded waters at the surface absorb CO₂ as they grow. When they die, they sink, bringing the carbon they’ve sequestered with them, making room for more CO₂ to be absorbed at the surface.

“The ocean’s response to the extreme temperatures of 2023 can be understood as the result of a permanent tug-of-war between temperature-induced outgassing and the concurrent depletion of dissolved CO₂,” says Gruber.

El Niño effect overlaid

The study also explains the influence of the 2023 El Niño on the marine carbon sink in a similar manner: During El Niño years, circulation in the tropical Pacific weakens, preventing cold, CO₂-rich water from rising to the surface. As a result, the tropical eastern Pacific, which in normal years releases very large amounts of CO₂ into the atmosphere, emits essentially no CO₂ during El Niño years. As a result, El Niño tends to enhance the global ocean CO₂ sink.

In 2023, however, this positive effect was overwhelmed by what happened elsewhere. While El Niño was causing reduced CO₂ emission from the ocean in the tropics, extreme warming in the North Atlantic and other regions caused such intense CO₂ release that it more than cancelled out the changes from the tropics.

The future of the marine sink remains uncertain

The researchers say it’s too early to know with certainty how this important carbon sink will evolve in the future as the global climate warms, and whether the compensating mechanisms will continue to counteract the temperature-driven outgassing of CO₂. The temperature records set in 2023 were surpassed in 2024, so the world’s oceans have hardly cooled down since the researchers first gathered data for the study.

“For the time being, however, the global ocean is still absorbing a great deal of CO₂, fortunately,” says Gruber.

Source link

Columbia Climate School news.climate.columbia.edu