A forthcoming Supreme Court decision is poised to weaken a bedrock law that requires federal agencies to study the potential environmental impacts of major projects.

The case, Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County, Colorado, concerns a proposed 88-mile railroad that would link an oil-producing region of Utah to tracks that reach refineries in the Gulf Coast. Environmental groups and a Colorado county argued that the federal Surface Transportation Board failed to adequately consider climate, pollution, and other effects as required under the National Environmental Protection Act, or NEPA, in approving the project. In 2023, the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the challengers. The groups behind the railway project, including several Utah counties, appealed the case to the highest court, which is expected to hand down a decision within the next few months.

Court observers told Grist the Supreme Court will likely rule in favor of the railway developers, with consequences far beyond Utah. The court could limit the scope of environmental harms federal agencies have to consider under NEPA, including climate impacts. Depending on how the justices rule, the decision could also bolster — or constrain — parallel moves by the Trump administration to roll back decades-old regulations governing how NEPA is implemented.

“All of these rollbacks and attacks on NEPA are going to harm communities, especially those that are dealing with the worst effects of climate change and industrial pollution,” said Wendy Park, senior attorney at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, a party in the Supreme Court case.

Since 1970, NEPA has required federal agencies to take a “hard look” at the environmental effects of proposed major projects or actions. Oil and gas pipelines, dams, mines, highways, and other infrastructure projects must undergo an environmental study before they can get federal permits, for example. Agencies consider measures to reduce potential impacts during their review and can even reject a proposal if the harms outweigh the benefits.

NEPA ensures that environmental concerns are “part of the agenda” for all federal agencies — even ones that don’t otherwise focus on the environment, said Dan Farber, a law professor at the University of California Berkeley. It’s also a crucial tool for communities to understand how a project will affect them and provide input during the decision-making process, according to Park.

John Carl D’Annibale / Albany Times Union via Getty Images

In 2021, the Surface Transportation Board, a small federal agency that oversees railways, approved a line that would connect the Uinta Basin to the national rail network. The basin, which contains large deposits of crude oil, spans about 12,000 square miles across northeastern Utah and northwestern Colorado and is currently accessible only by truck. The proposed track would allow companies to transport crude oil to existing refineries along the Gulf Coast, quadrupling waxy crude oil production in the basin. According to the agency’s environmental review, under a high oil production scenario, burning those fuels “could represent up to approximately 0.8 percent of nationwide emissions and 0.1 percent of global emissions” — about 30 million tons of carbon dioxide a year.

Environmental groups and a Colorado county challenged the board’s approval at the D.C. Circuit Court. The groups argued that the agency had failed to consider key impacts in its NEPA review, including the effects of increased oil refining on communities already burdened by pollution along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Texas, and the potential for more oil spills and wildfires along the broader rail network. In August 2023, the D.C. Circuit largely agreed, finding “numerous NEPA violations” in the agency’s environmental review.

In their appeal to the Supreme Court, the developers of the railway initially argued that an agency shouldn’t have to consider any environmental effects of a project that would fall under the responsibility of a different agency. In this case, for example, the Surface Transportation Board wouldn’t have to consider air pollution impacts of oil refining on Gulf Coast communities because the Environmental Protection Agency, not the Surface Transportation Board, regulates air pollution.

By oral arguments in December, however, the railway backers had walked away from this drastic interpretation, which contradicts decades of NEPA precedent. It’s standard practice for one agency’s environmental review to study impacts that fall under the responsibility of other agencies, said Deborah Sivas, a law professor at Stanford University. The railway proponents instead proposed that agencies shouldn’t have to consider impacts that fall outside of their authority and are “remote in time and space.” That would include the effects on Gulf Coast communities residing thousands of miles away — as well as climate impacts like greenhouse gas emissions.

Park, from the Center for Biological Diversity, argued that overlooking those impacts would undermine the intent of NEPA, which is to inform the public of likely harms. “The entire purpose of this project is to ramp up oil production in Utah and to deliver that oil to Gulf Coast refineries,” she said. “To effectively allow the agency to turn a blind eye to that purpose and ignore all of the predictable environmental harms that would result from that ramped-up oil production and downstream refining is antithetical to NEPA’s purpose.”

Lawyers for the railway’s developers didn’t respond to Grist’s request for comment. A coalition of Utah counties backing the project has previously underlined the economic potential of the project. “We are optimistic about the Supreme Court’s review and confident in the thorough environmental assessments conducted by the STB,” said Keith Heaton, director of the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition, said in a statement after the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. “This project is vital for the economic growth and connectivity of the Uinta Basin region, and we are committed to seeing it through.”

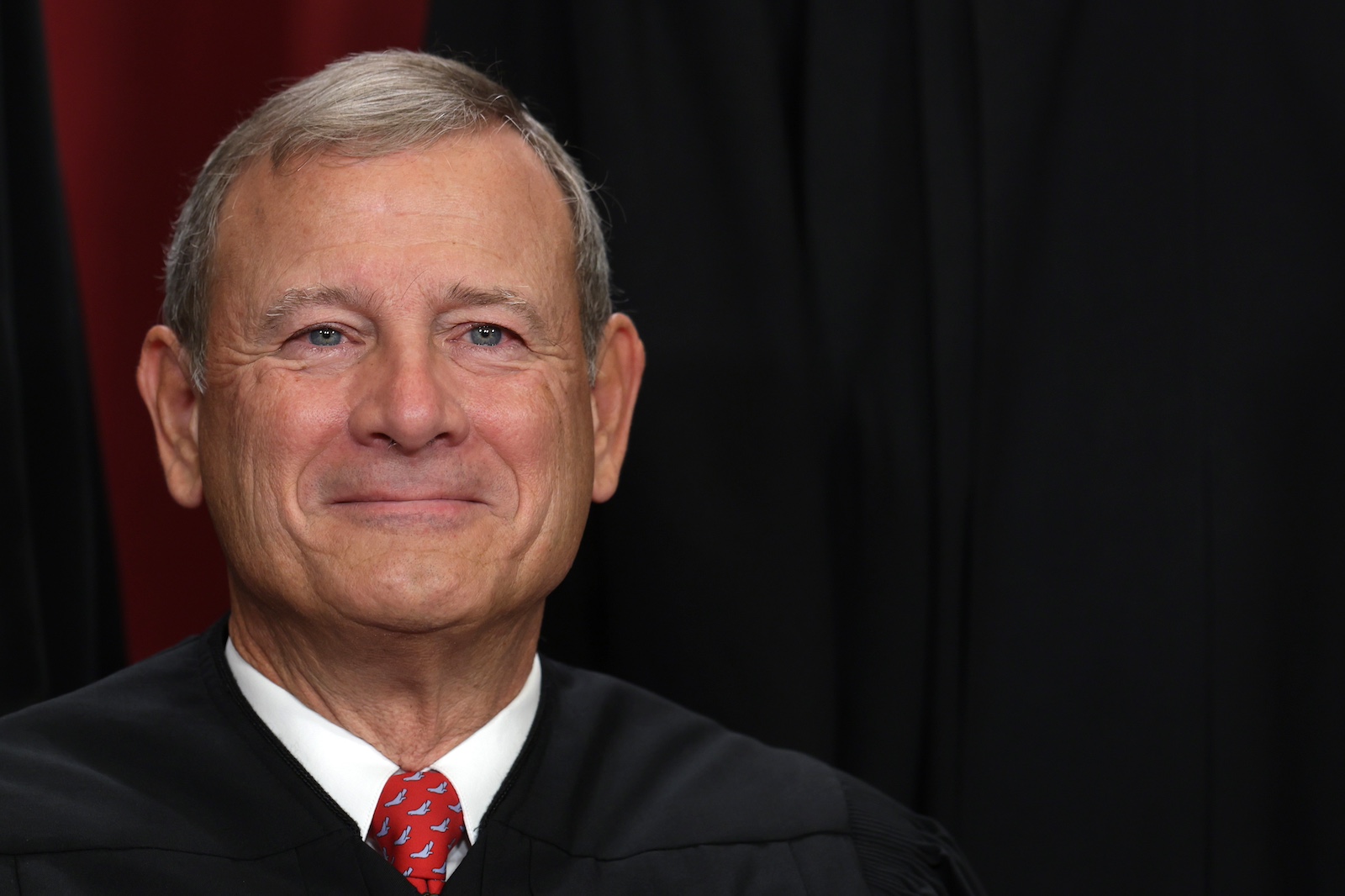

The Supreme Court has historically always ruled in favor of the government in NEPA cases, and legal experts told Grist the decision will likely support the railway developers in some manner. But during oral arguments, several justices seemed skeptical of positions presented by railway supporters. Chief Justice John Roberts noted that imposing such severe limits on NEPA review could open agencies up to legal risk.

Alex Wong / Getty Images

The court could reach some kind of middle ground in its decision — not going as far as the D.C. Circuit to affirm the legitimacy of considering a wide range of climate and other risks, but also not excluding as many impacts as the railway developers had hoped, said Farber.

Any decision will ultimately serve as an important guide for agencies as the Trump administration introduces even more uncertainty in the federal permitting process. In February, the administration issued an interim rule to rescind regulations issued by the White House Council on Environmental Quality, which oversees NEPA implementation across the federal government. The council’s rules have guided agencies in applying the law for nearly five decades. Now, Trump officials have left it up to each individual agency to develop its own regulations by next February.

In developing those standards, agencies will likely look to the Supreme Court’s decision, legal experts said. “What the Supreme Court rules here could be a very important guide as to how agencies implement NEPA and how they fashion their regulations interpreting NEPA,” said Park. If the court rules that agencies don’t need to consider climate impacts in NEPA reviews, for example, that could make it easier for Trump appointees to ignore greenhouse gas emissions, said Sivas. The White House has already instructed agencies not to include environmental justice impacts in their assessments.

On the other hand, a more nuanced opinion by the Supreme Court could end up undercutting efforts by the Trump administration to limit the scope of environmental reviews, said Farber. If justices end up affirming the need to consider certain impacts of the Utah railway project, for example, that could limit how much agencies under Trump can legally avoid evaluating particular effects. Agencies need to design regulations that will withstand challenges in lower courts — which will inevitably rely on the Supreme Court’s ruling when deciding on NEPA challenges moving forward.

In the meantime, however, legal experts say that Trump’s decision to have each agency create its own NEPA regulations will create even more chaos and uncertainty, even as the administration seeks to “expedite and simplify the permitting process” through sweeping reforms.

“I think that’s going to just slow down the process more and cause more confusion, and not really serve their own goals,” said Farber.

Source link

Akielly Hu grist.org