1. Introduction

Due to the rapid rise in the global population, natural resources are facing increasing pressure. Meanwhile, traditional agriculture based on high inputs and outputs from natural resources, the use of intensive farming practices, and the extensive usage of irrigation are having a significant impact on the global environment. Ensuring food security is thus the primary issue for global development [

1,

2,

3,

4], which centers on the efficient use of agricultural water–soil resources [

5]. Indeed, many global regions, such as arid and semi-arid areas, face similar resource scarcity challenges, and solutions including increased agricultural mechanization and the optimization of irrigation practices have already been proposed worldwide [

6,

7,

8]. Globally, 20% of arable land is currently irrigated, contributing 40% of food production, while agriculture accounts for 90% of the total water consumption [

6]. With the liberalization of global food trade and rising food demand, the importance of matching water–soil resources has become more prominent, and food security and sustainable agricultural development are global challenges [

8,

9]. China is one of the largest agricultural countries globally, but its spatial distribution of water–soil resources is inefficient, with major grain-producing areas located in northern regions where water–soil resources are limited. This adversely affects the country’s food security and significantly hinders the development of the regional economy [

10,

11]. The effective allocation of water–soil resources is therefore crucial to dynamic and spatial distribution in grain production.

However, there is still limited understanding of how the interplay between water and soil resources affects food production, particularly from a spatial perspective that integrates physical water and water footprint. This understanding is essential to the effective planning of water–soil resources to ensure sustainable food production and food security. The water footprint, bridging physical and virtual water, is commonly used to quantify the relationship between food production and water consumption, offering insights into agricultural water use and its utilization efficiency [

12]. It has been widely employed to estimate water consumption for various crops at both global and regional scales [

13]. In this study, we therefore examine regional grain–water–soil resource matching from a “physical water–water footprint” perspective, aiming to thoroughly understand the matching characteristics and relationships among them.

Water–soil matching is a quantitative relationship that characterizes the appropriate alignment of the water required for agricultural production and cultivated land in time and space, which plays a decisive role in agricultural production [

2]. Its spatial distribution pattern is the foundation for sustainable socio-economic development and agricultural production, and plays an important role in guaranteeing regional food security. Existing research has explored the relationship between water–soil and grain production at global and regional levels, focusing on analyzing single resources, such as water and soil, as well as the coupling relationships and interaction among these elements [

10,

14,

15]. Additionally, researchers have explored the patterns and characteristics of water–soil resource matching in specific regions across different spatial and temporal scales [

16,

17]. Most studies have adopted the Gini coefficient [

18,

19], Markov chain [

20], and water–soil resource matching coefficient [

10,

21] methods, focusing on global water shortage regions and major grain-producing areas such as the Bima River Basin, the arid areas of northwestern China, the Yellow River Basin, northeastern China, and typical mountainous areas in India; emphasizing regional grain production, cultivated land changes, and the matching of water–soil resources with socio-economic factors; and proposing targeted suggested measures.

Previous studies have made substantial progress in understanding the matching of water–soil and spatial heterogeneity in grain production. However, the following research gaps still exist: (1) From a research perspective, the binary matching characteristics of the three key elements of “water–soil–grain” in grain production have not been thoroughly explored, particularly from the integrated physical water–water footprint perspective. (2) From the methodological perspective, traditional econometric models often overlook the definition of a reasonable range for water–soil matching across different regions, typically assuming that a larger matching coefficient always leads to better outcomes; however, this is actually not the case. In contrast, this study abandons the simplistic notion that a higher water–soil matching coefficient is always advantageous. Instead, we calculate the range of reasonable water–soil matching coefficients for high-yield targets by using field trial data, an approach that defines the optimal scope of the crop-planting structure from the water footprint perspective. By doing so, we provide critical data for assessing the degree of water–soil matching in grain production and enhance the understanding of water–soil utilization across various grain crop production systems. Moreover, this methodology lays the foundation for agricultural zoning and planting strategies in irrigated regions.

The NCP is the region with the highest degree of development of water and soil resource utilization in China [

22]. As the primary grain-producing area, it has the world’s largest groundwater drop funnel. Groundwater, which accounts for approximately 70% of the total water supply, serves as the main water source [

23]. However, the overexploitation of groundwater for agricultural production has led to various environmental geological issues, thereby restricting the sustainable development of the social economy [

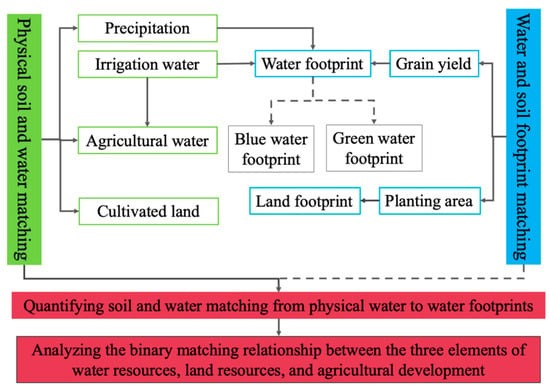

19]. In response, in this study, we comprehensively analyzed key agricultural and water-related data in the NCP, including precipitation, the yield of five major grain crops (wheat, corn, rice, soybean, and potato), the planting area, the cultivated area, and irrigation from 1950 to 2022. Firstly, the binary matching characteristics of the three elements of water, soil, and agricultural development were determined from the perspective of “physical water”. Secondly, based on the “water footprint” approach, the water–soil matching coefficient method was applied to quantitatively analyze the water–soil matching patterns of these five major grain crops for the years 1984, 1998, 2003, and 2022. Finally, from the “physical water–water footprint” coupling perspective, field experimental data on wheat, corn, soybean, and potato were used to calculate the range of reasonable water–soil matching coefficients for high yields. The spatial distribution of groundwater funnels was analyzed, providing a scientific basis for evaluating the matching of water–soil resources and supporting their sustainable use. The research framework is shown in

Figure 1.

The research objectives are as follows:

- (1)

Explore the water–soil matching of grain production in the NCP from the physical water–water footprint perspective.

- (2)

Calculate the reasonable range of the water–soil matching coefficient of grain in the NCP.

- (3)

Assess the impact of the elastic range of the water–soil matching coefficient on the optimization and adjustment of the crop-planting structure.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we systematically investigate the roles of physical water and water footprint in agricultural water–soil matching research in the NCP, employing geospatial analysis techniques and the water–soil matching coefficient model. From the perspectives of physical water and water footprint, we assess the water–soil matching of grain crops in the NCP, providing empirical evidence for ensuring food security. The following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

The natural water–soil matching in the NCP exhibited spatial misalignment. From 1949 to 2022, grain production and planting area showed an increasing trend, with average annual growth rates of 3.96% and 0.6%, respectively. Wheat yields were the highest, followed by those of corn, potato, and rice, and soybean yields were the lowest.

- (2)

The water footprint of grain in the NCP still has room for further optimization, with the total water footprint increasing at an average annual growth rate of 3.74%. The annual proportion of the total blue water footprint (57.85%) consistently exceeded that of the green water footprint (38.38%). Spatially, the water footprints displayed overlapping patterns, with higher values in the central and southern regions and lower values in the northern areas. Regions with high water footprints had a larger proportion of wheat cultivation.

- (3)

By using field trial data, the critical range of the water–soil matching coefficient under irrigation water constraints in the NCP was calculated to be between 0.534 and 0.724. Currently, regional water–soil matching coefficients far exceed this critical range, indicating that the land distribution is concentrated, agricultural water resources are scarce, and groundwater extraction intensity is high. The proportion of wheat and rice matching coefficients in the area with a high soil–water matching coefficients was also higher. The overlap between major grain-producing areas and the groundwater depletion zones was evident.

The water–soil matching coefficient is a key metric for evaluating the suitability of water–soil resources for regional agriculture. In this study, we examine the spatio-temporal variation characteristics of major food crop and cultivated land water footprints in China, as well as their matching relationships. In terms of resource efficiency, improving water–soil matching should focus on two aspects: reducing the planting area of water-intensive crops such as wheat and rice, and promoting water-saving irrigation technologies like drip irrigation. In the short term, the government should discourage planting high-value crops in high-value areas through subsidies or ecological compensation measures, and establish corresponding water–soil matching monitoring mechanisms based on the growth cycles of different crops to adjust the crop planting structure according to local conditions. In the long term, relevant government departments should establish different levels of regulation areas based on the matching coefficient. In addition, the bottom line for crop water use should be set, and farmers should be encouraged to adopt water-retaining agricultural technologies to enhance the soil’s water retention capacity.