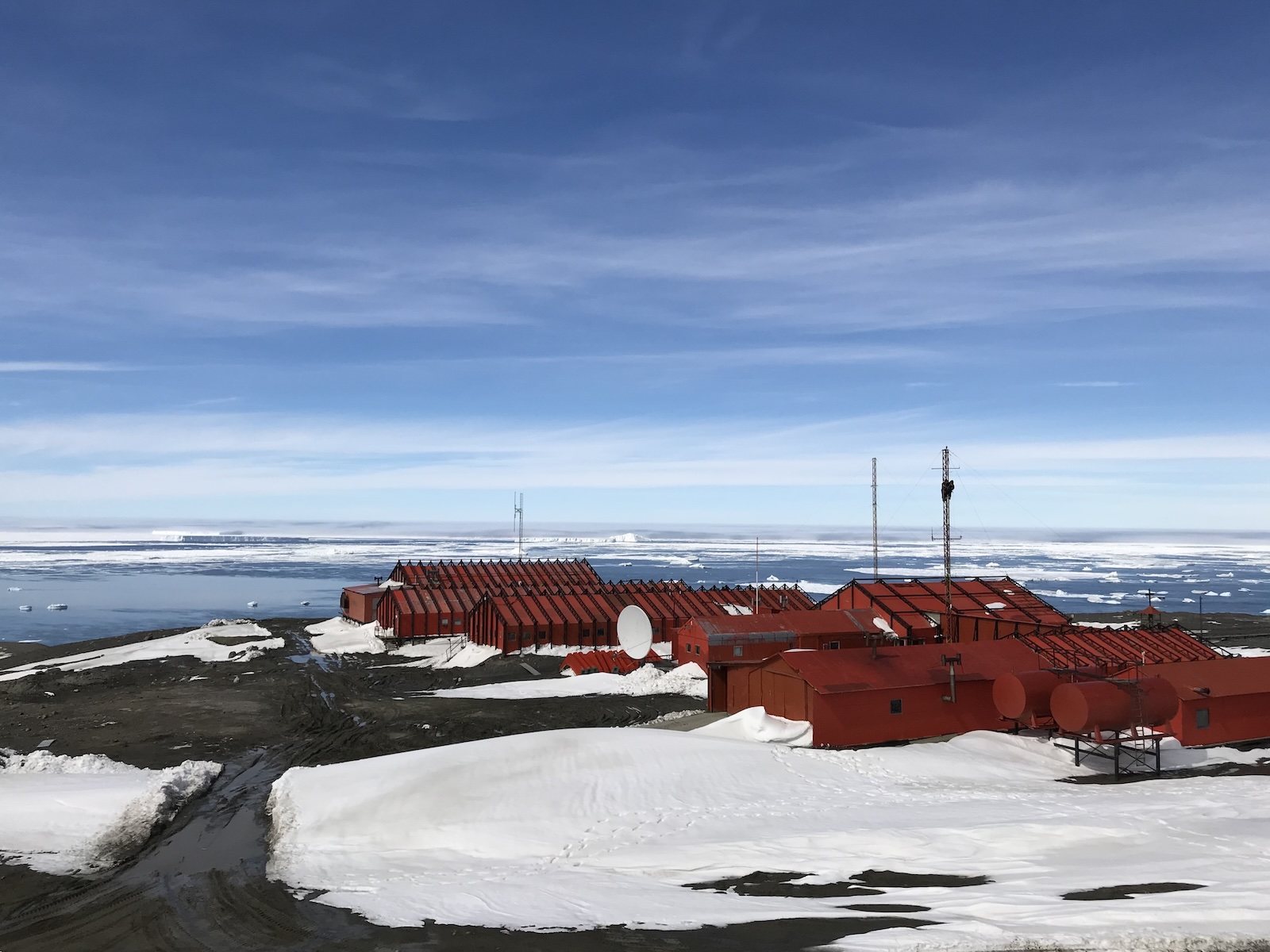

In December 2022, Matthew Boyer hopped on an Argentine military plane to one of the more remote habitations on Earth: Marambio Station at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, where the icy continent stretches toward South America. Months before that, Boyer had to ship expensive, delicate instruments that might get busted by the time he landed.

“When you arrive, you have boxes that have been sometimes sitting outside in Antarctica for a month or two in a cold warehouse,” said Boyer, a Ph.D. student in atmospheric science at the University of Helsinki. “And we’re talking about sensitive instrumentation.”

But the effort paid off, because Boyer and his colleagues found something peculiar about penguin guano. In a paper published on Thursday in the journal Communications Earth and Environment, they describe how ammonia wafting off the droppings of 60,000 birds contributed to the formation of clouds that might be insulating Antarctica, helping cool down an otherwise rapidly warming continent. Some penguin populations, however, are under serious threat because of climate change. Losing them and their guano could mean fewer clouds and more heating in an already fragile ecosystem, one so full of ice that it will significantly raise sea levels worldwide as it melts.

A better understanding of this dynamic could help scientists hone their models of how Antarctica will transform as the world warms. They can now investigate, for instance, if some penguin species produce more ammonia and, therefore, more of a cooling effect. “That’s the impact of this paper,” said Tamara Russell, a marine ornithologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who studies penguins but wasn’t involved in the research. “That will inform the models better, because we know that some species are decreasing, some are increasing, and that’s going to change a lot down there in many different ways.”

With their expensive instruments, Boyer and his research team measured atmospheric ammonia between January and March 2023, summertime in the southern hemisphere. They found that when the wind was blowing from an Adelie penguin colony 5 miles away from the detectors, concentrations of the gas shot up to 1,000 times higher than the baseline. Even when the penguins had moved out of the colony after breeding, ammonia concentrations remained elevated for at least a month, as the guano continued emitting the gas. That atmospheric ammonia could have been helping cool the area.

The researchers further demonstrated that the ammonia kicks off an atmospheric chain reaction. Out at sea, tiny plantlike organisms known as phytoplankton release the gas dimethyl sulfide, which transforms into sulphuric acid in the atmosphere. Because ammonia is a base, it reacts readily with this acid.

Lauriane Quéléver

This coupling results in the rapid formation of aerosol particles. Clouds form when water vapor gloms onto any number of different aerosols, like soot and pollen, floating around in the atmosphere. In populated places, these particles are more abundant, because industries and vehicles emit so many of them as pollutants. Trees and other vegetation spew aerosols, too. But because Antarctica lacks trees and doesn’t have much vegetation at all, the aerosols from penguin guano and phytoplankton can make quite an impact.

In February 2023, Boyer and the other researchers measured a particularly strong burst of particles associated with guano, sampled a resulting fog a few hours later, and found particles created by the interaction of ammonia from the guano and sulphuric acid from the plankton. “There is a deep connection between these ecosystem processes, between penguins and phytoplankton at the ocean surface,” Boyer said. “Their gas is all interacting to form these particles and clouds.”

But here’s where the climate impacts get a bit trickier. Scientists know that in general, clouds cool Earth’s climate by reflecting some of the sun’s energy back into space. Although Boyer and his team hypothesize that clouds enhanced with penguin ammonia are probably helping cool this part of Antarctica, they note that they didn’t quantify that climate effect, which would require further research.

That’s a critical bit of information because of the potential for the warming climate to create a feedback loop. As oceans heat up, penguins are losing access to some of their prey, and colonies are shrinking or disappearing as a result. Fewer penguins producing guano means less ammonia and fewer clouds, which means more warming and more disruptions to the animals, and on and on in a self-reinforcing cycle.

“If this paper is correct — and it really seems to be a nice piece of work to me — [there’s going to be] a feedback effect, where it’s going to accelerate the changes that are already pushing change in the penguins,” said Peter Roopnarine, curator of geology at the California Academy of Sciences.

Scientists might now look elsewhere, Roopnarine adds, to find other bird colonies that could also be providing cloud cover. Protecting those species from pollution and hunting would be a natural way to engineer Earth systems to offset some planetary warming. “We think it’s for the sake of the birds,” Roopnarine said. “Well, obviously it goes well beyond that.”

Source link

Matt Simon grist.org