Since 2019, the 191 countries that are party to an international agreement called the Basel Convention have agreed to classify mixed plastic trash as “hazardous waste.” This designation essentially bans the export of unsorted plastic waste from rich countries to poor countries and requires it to be disclosed in shipments between poor countries. But the rule has a big loophole.

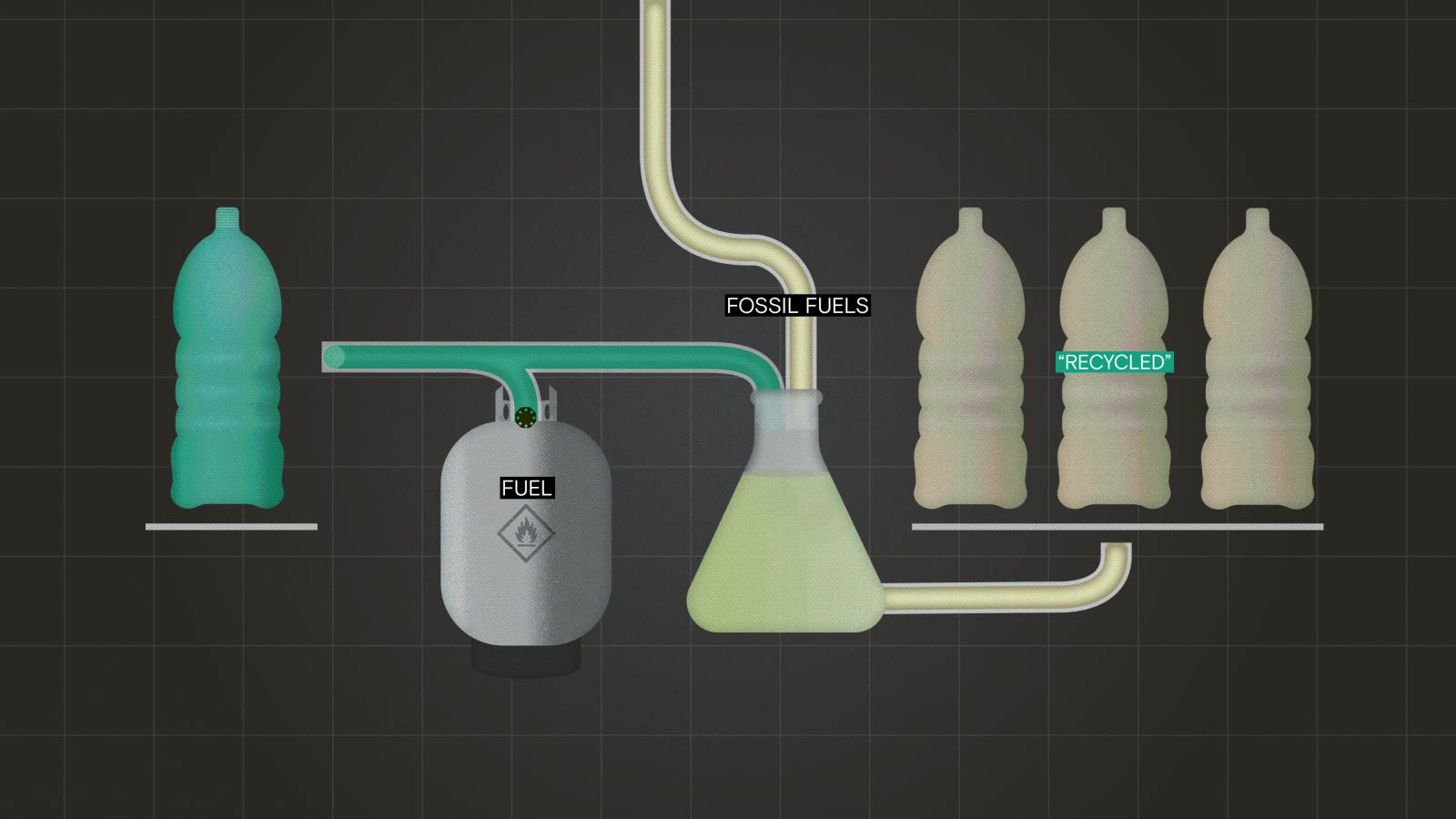

Every year, an unknown but potentially large amount of plastic waste continues to be traded in the form of “refuse-derived fuel,” or RDF, ground-up packaging and industrial plastic waste that gets mixed with scrap wood and paper in order to be burned for energy. Environmental groups say these exports perpetuate “waste colonialism” and jeopardize public health, since burning plastic emits hazardous pollutants and greenhouse gases that warm the planet.

Many advocates would like to see the RDF loophole closed as a first step toward discouraging the development of new RDF facilities worldwide. They were disappointed that, at this spring’s biannual meeting of the Basel Convention — the 1989 treaty that regulates the transboundary movement of hazardous waste — RDF went largely unaddressed. “It’s just frustrating to witness all these crazy, profit-protecting negotiators,” said Yuyun Ismawati, co-founder of the Indonesian anti-pollution nonprofit Nexus3. “If we are going to deal with plastic waste through RDF, then … everybody must be willing to learn more about what’s in it.”

RDF is a catch-all term for several different products, sometimes made with special equipment at material recovery facilities — the centers that, in the U.S., receive and sort mixed household waste for further processing. ASTM International, an American standard-setting organization, lists several types of RDF depending on what it’s made of and what it’s formed into — coarse particles no larger than a fingernail, for example, or larger briquettes. Some RDF is made by shredding waste into a loose “fluff.”

Although RDF contains roughly 50 percent paper, cardboard, wood, and other plant material, the rest is plastic, including human-made textiles and synthetic rubber. It’s this plastic content that makes RDF so combustible — after all, plastics are just reconstituted fossil fuels. According to technical guidelines from the Basel Convention secretariat, RDF contains about two-thirds the energy of coal by weight.

One of the main users of RDF is the cement industry, which can burn it alongside traditional fossil fuels to power its energy-intensive kilns. Álvaro Lorenz, global sustainability director for the multinational cement company Votorantim Cimentos, said RDF has gained popularity as cities, states and provinces, and countries struggle to deal with the 353 million metric tons of plastic waste produced each year — 91 percent of which is never recycled. Some of these jurisdictions have implemented policies discouraging trash from being sent to landfills. Instead, it gets sent to cement kilns like his. “Governments are promoting actions to reduce the amount of materials being sent to landfills, and we are one solution,” he said.

Matt Hunt / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Lorenz said RDF makes his company more sustainable by contributing to a “circular economy.” In theory, using RDF instead of coal or natural gas reduces emissions and advances companies’ environmental targets. According to David Araujo, North America engineered fuels program manager for the waste management and utility company Veolia, RDF produced by his company’s factory in Louisiana, Missouri, allows cement company clients in the Midwest to avoid 1.06 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions with every ton of RDF burned. The ash produced from burning RDF can also be used as a raw material in cement production, he added, displacing virgin material use.

RDF is also attractive because it is less price-volatile than the fossil fuels that cement production would otherwise depend on. In one analysis of Indonesian RDF production from last year, researchers found that each metric ton of RDF can save cement kiln operators about $77 in fuel and electricity costs.

Lorenz said that the high temperatures inside cement kilns “completely burn 100 percent” of any hazardous chemicals that may be contained in RDF’s plastic fraction. But this is contested by environmental advocates who worry about insufficiently regulated toxic air emissions similar to those produced by traditional waste incinerators — especially in poor countries with less robust environmental regulations and enforcement capacity. Dioxins, for example, are released by both cement kilns and other waste incinerators, and are linked to immune and nervous system impairment. Burning plastic can also release heavy metals that are associated with respiratory and neurological disorders. A 2019 systematic review of the health impacts of waste incineration found that people living and working near waste incinerators had higher levels of dioxins, lead, and arsenic in their bodies, and that they often had a higher risk of some types of cancer such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

“Before they convert it into fuel, the chemicals are still locked inside the [plastic] packaging,” said Ismawati. “But once you burn it, … you spray out everything.” She said some of her friends living near an RDF facility in Indonesia have gotten cancer, and at least one has died from it.

Lorenz and Araujo both said their companies are subject to, and comply with, applicable environmental regulations in the countries where they operate.

Lee Bell, a science and policy adviser for the International Pollutants Elimination Network — a network of environmental and public health experts and nonprofits — also criticized the idea that burning RDF causes fewer greenhouse gas emissions than burning traditional fossil fuels. He said this notion fails to consider the “petrochemical origin” of plastic waste: Plastics cause greenhouse gas emissions at every stage of their life cycle, and, as a strategy for dealing with plastic waste, research suggests that incineration releases more climate pollution than other waste management strategies. In a landfill, where plastic lasts hundreds of years with little degradation, the nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law has estimated greenhouse gas emissions at about 132 pounds per metric ton. That rises to about 1,980 pounds of emissions per metric ton when plastic is incinerated.

Bell said he’s concerned about the apparent growth of the RDF industry worldwide, though there is little reliable data about how much of the stuff is produced and traded between countries each year. Part of the problem is the “harmonized system” of export codes administrated by the World Customs Organization, which represents more than 170 customs bodies around the world. The organization doesn’t have a specific code for RDF and instead lumps it with any of several other categories — ”household waste,” for example — when it’s traded internationally. Only the U.K. seems to provide transparent reporting of its RDF exports. In the first three months of 2025 it reported sending about 440,000 metric tons abroad, most of which was received by Scandinavian countries.

Nearly all of the world’s largest cement companies already use RDF in at least some of their facilities. According to one market research firm, the market for RDF was worth about $5 billion in 2023, and it’s expected to grow to $10.2 billion by 2032. Other firms have forecast a bright outlook for the RDF industry in the Middle East and Africa, and one analysis from last year said that Asia is “realizing tremendous potential as a growth market for RDF” as governments seek new ways to manage their waste. Within the past year, new plans to use RDF in cement kilns have been announced in Peshawar, Pakistan; Hoa Binh, Vietnam; Adana, Turkey; and across Nigeria, just to name a few places.

Peter Titmuss / UCG / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Araujo, with Veolia, said his company’s RDF program “has grown exponentially” over the past several years, “and we recently invested millions of dollars to upgrade equipment to keep pace with demand.” A separate spokesperson said Veolia does not send RDF across international borders, and a spokesperson for Votorantim Cimentos said the company always sources RDF locally.

Dorothy Otieno, a program officer at the Nairobi-based Centre for Environment Justice and Development, said investment in RDF infrastructure could create a perverse incentive for the world to create more plastic — and for developing countries to import it — just to ensure that facility operators earn a return on their investment. “Will this create an avenue for the importation of RDFs and other fossil fuel-based plastics?” she asked. “These are the kinds of questions that we are going to need to ask ourselves.”

At this year’s Basel Convention conference in May and June, the International Pollutants Elimination Network called for negotiators to put RDF into the same regulatory bucket as other forms of mixed plastic — potentially by classifying it as hazardous waste. Doing so would prohibit rich countries from exporting RDF to poor ones, and make its trade between developing countries contingent on the receiving country giving “prior informed consent.”

Negotiators fell short of that vision. Instead, they requested that stakeholders — such as RDF companies and environmental groups — submit plastic waste-related comments to the secretariat of the Basel Convention, for discussion at a working group meeting next year. Bell described this as “kicking the cans down the road.”

“This is disappointing,” he added. “We appear to be on the brink of an explosion in the trade of RDF.”

The next Basel Convention meeting isn’t until 2027. But in the meantime, countries are free to create their own legislation restricting the export of RDF. Australia did this in 2022 when, following pressure from environmental groups, it amended its rules for plastic waste exports. The country now requires companies to obtain a hazardous waste permit in order to send a type of RDF called “process engineered fuel” abroad. Although RDF exports to rich countries like Japan continue, the new requirements effectively ended the legal export of RDF from Australia to poorer countries in Southeast Asia.

Ultimately, Ismawati said countries need to focus on reducing plastic production to levels that can be managed domestically — without any type of incineration. “Every country needs to treat waste in their own country,” Ismawati said. “Do not export it under the label of a ‘circular economy.’”

Source link

Joseph Winters grist.org