Lexi Shelhorse is a seventh-generation resident of Pittsylvania County, Virginia, where she grows hay on family farmland in Whittles, a rural community in the southern part of the state. She can trace her lineage back to Johann Barnett Shelhousen, a German immigrant who arrived during the United States Revolutionary War in the 1790s and bought 150 acres of land that would be used by his descendants for growing tobacco and raising cattle. While the plot Shelhorse currently lives on is down the road from her ancestors’ original settlement, her connection to the land is strong.

On a weeknight last October, Shelhorse got a call: The land that had been in her family for generations was set to be destroyed. Plans were underway for a 2,200-acre gas-powered data center campus that, if approved by the county’s Board of Supervisors, would be the largest in Virginia and the second-largest in the U.S.

The initial proposal, made by Balico, LLC, a company based just outside of Washington, D.C., in Herndon, Virginia, included plans for 84 warehouse-sized data center buildings and a 3,500-megawatt power plant fueled by natural gas. Balico’s initial application also requested to rezone 14 parcels of land it had purchased from landowners, which were zoned for agricultural and rural residential use.

“People went into panic mode,” said Amanda Wydner, a lifelong Pittsylvania County resident who was on the other end of the line with Shelhorse, her neighbor and friend. “It appeared that it truly was going to swallow up a region and create a patchwork-quilt style of development.”

Northern Virginia has been dubbed the “Data Center Capital of the World,” with 507 data centers located north of Richmond, Virginia, a higher concentration than in any other state or country. Artificial intelligence, or AI, is driving a sharp increase in power demand from data centers, which are critical for powering the large language models on which the technology is built. These giant buildings house the computers and servers necessary to store and send information, and they can consume millions of gallons of water each day.

Cornelius Lewis / SELC

Domestic power demand from data centers is expected to double or triple by 2028 compared to 2023 levels, per a December 2024 U.S. Department of Energy report. In Virginia, developers seeking to bring new facilities online are venturing beyond the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area to rural communities in the southern part of the state. There, land comes at a lower cost than up north, making it attractive for building campuses with thousand-acre footprints.

The push to develop data centers in rural areas is a growing trend across the country, particularly in the Southeast. Recently, proposed data center campuses in Bessemer, Alabama; Davis, West Virginia; and Oldham County, Kentucky, have all drawn local opposition. A common thread is developers limiting public access to information about the projects.

For Pittsylvania County’s Shelhorse and Wydner, these stories are all too familiar — and frustrating. Shelhorse remembers what it felt like when she first got the phone call from Wydner. “It made me angry,” said Shelhorse. “It seems like people from the north are trying to scout the southern communities because they’ve run out of land.”

That anger breeds resistance among rural communities facing similar challenges across the U.S. But grassroots opposition isn’t always successful.

In southern Virginia, however, thanks to the efforts of Wydner, Shelhorse, and a few others determined to preserve the quality of life they say is rooted in their landscape, Pittsylvania’s local government rejected Balico’s request to rezone the land for data centers back in April 2025. The county then barred the company, which owns the land, from submitting another request until the spring of 2026.

The move comes after a monthslong struggle between residents and the developer, one that involved support from attorneys at the Southern Environmental Law Center and air pollution researchers at Harvard University. While the decision feels like a success for those who opposed the development, Shelhorse cautions that the struggle isn’t over.

“We won the battle, but not the war,” she said. Within that battle, though, lies a roadmap for others who could find themselves facing off with developers seeking to build vast complexes that border — or slice right through — rural communities.

‘Get in the fight early’

To begin with, Wydner and Shelhorse said it’s critical to get in the fight early. They encouraged other rural communities to keep tabs on their local government, since that’s often where decisions happen.

“Engagement in local government is imperative,” Wydner said. “If we had pulled back in any way, there’s a possibility that the Board would not have felt our opposition with such ferocity. But we never pulled back. We were very, very consistent.”

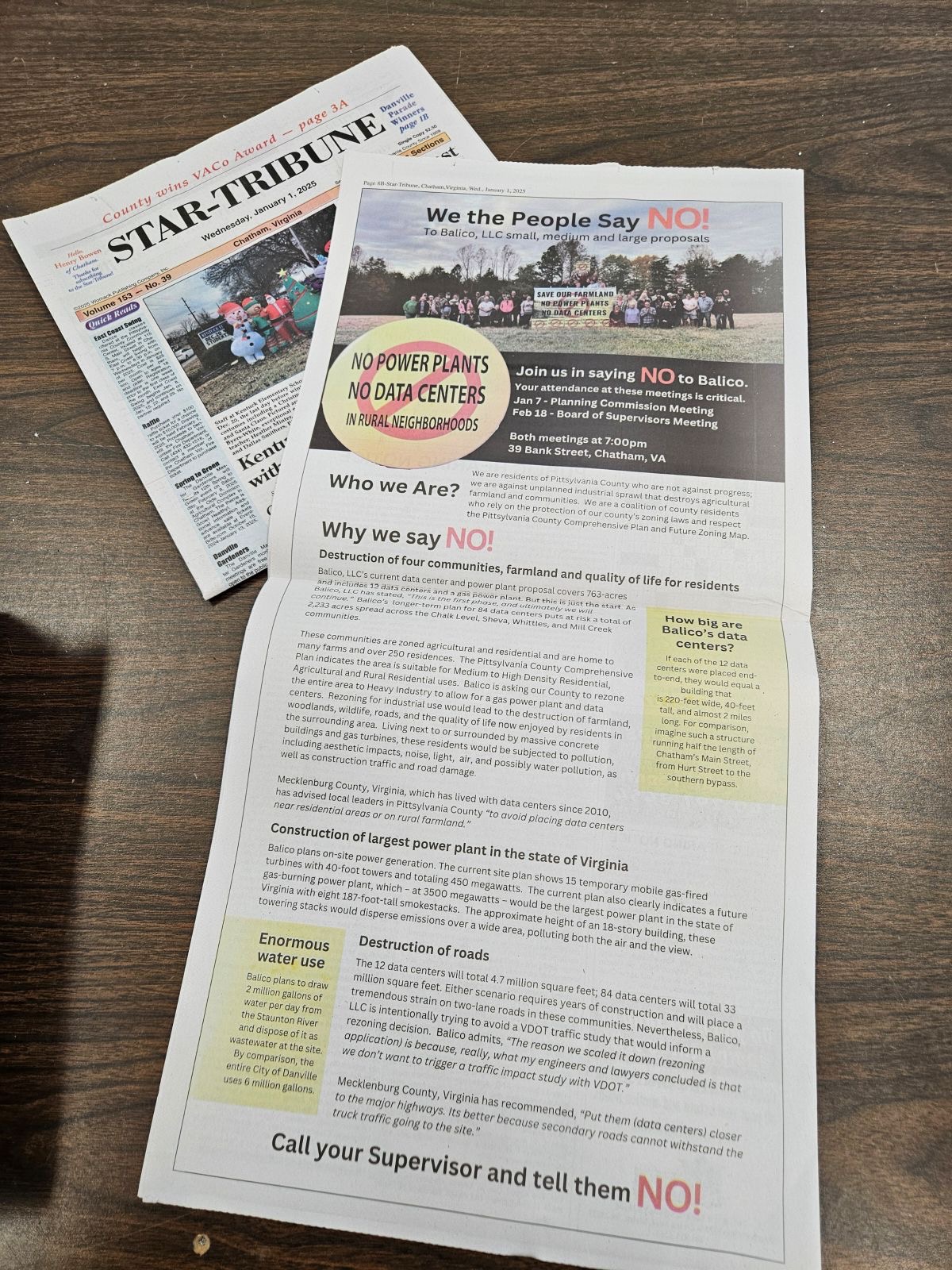

Two days after Shelhorse and Wydner’s phone call last October, they were joined by two dozen others at the county’s Community Development Office on October 18, 2024, to review maps and details about the proposed project. Wydner, whose family farmland also dates back generations, assembled the group after spotting a request in the local newspaper to rezone the county’s agricultural and residential land to accommodate 33 million square feet of data centers.

A county meeting to approve that request was scheduled for November 4. The opposition coalesced around Wydner shortly after the meeting at the Community Development Office. The group ordered yard signs opposing the development, organized meetings, and began researching Balico, the developer.

About a week later, 250 people crowded into Mill Creek Community Church, located on the edge of the proposed development, to strategize about their opposition. Kathy Stump was among the residents at the meeting. Like the church, Stump’s property was also in close proximity to the proposed data centers.

She lives along a windy two-lane road that was to be the primary transport route during construction. Far from being a major thoroughfare, Stump described having to pull to the side of the road to allow the milk trucks that frequent it to pass.

“I know there are needs for this, but there’s also places for these things,” said Stump. “There are industrial parks that these things need to go in — they don’t need to go up against homes and in residential areas.”

The land in Balico’s proposal was once at the heart of Pittsylvania County’s dairy industry. Landowners were approached by Balico as early as December 2023, and by the summer of 2024, contracts had been signed and the land exchanged hands. Nondisclosure agreements mean the exact offers made to landowners are not public, but residents estimate landowners were given double or triple the county’s typical per-acre value.

Between the Mill Creek Church gathering at the end of October and the November 4 meeting, the burgeoning local opposition held multiple events to spread the word about the data centers. Then, on the night of November 3, Balico pulled their proposal from the county’s consideration.

The developer came back with an amended version of their initial proposal a few weeks later. This time, Balico wanted to build 12 data centers on over 750 acres. The plans to build a 3,500-megawatt gas-fired power plant and rezone all of the land they’d purchased were unchanged. The group of concerned residents was wary.

“Right there in the rezoning was the open canvas for the 3,500-megawatt power plant,” said Wydner. “I hate to frame it as a game, but it almost became that way, like, ‘Hey, what can we get done to open the door to the big picture here? What can we get done to carve out this entire region as our own, personal, industrial mega-park?’”

By the end of 2024, Wydner and several others had connected with attorneys from the Southern Environmental Law Center, or SELC, an environmental legal advocacy organization in the South, for help.

The dirty truth about natural gas

Before Balico came along, “gas” was hardly a dirty word in Pittsylvania County. So when development plans included a proposal for a 3,500-megawatt gas-fired power plant, Wydner said that few alarm bells went off in the community, which she described as “solid red on voting day.”

“Most of us see broadcasts and commercials that speak to gas energy as clean energy, when, in fact, it’s cleaner than coal, but it is not necessarily clean energy,” she said.

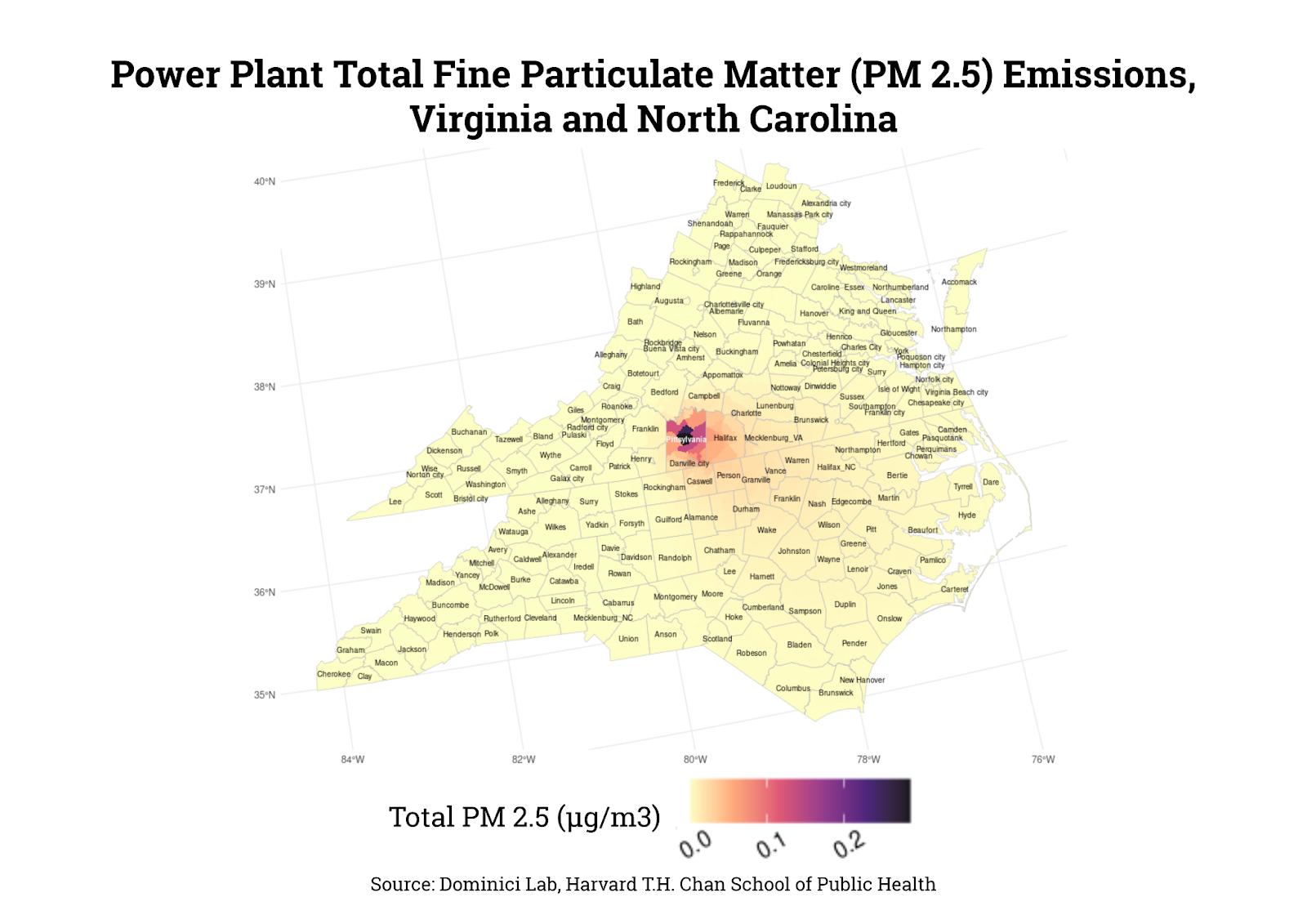

But, as Wydner and the rest of the local opposition would soon come to understand, a gas-fired power plant of the scale that Balico was proposing would have significant public health implications. Shortly after SELC got involved, researchers from the Dominici Lab at Harvard University’s School of Public Health went to work mapping the plant’s expected emissions of a particularly dangerous pollutant called fine particulate matter. No level of exposure to this kind of pollutant is safe, yet the researchers found that more than 1.2 million residents would face some amount of pollution across the Virginia-North Carolina line.

In Pittsylvania County, around 17,500 people, or more than 1 in 4 county residents, would face levels of exposure associated with increased hospitalizations due to heart attack, pneumonia, cardiovascular issues, and, in severe cases, stroke or cancer.

Keri Powell is SELC’s Air Program leader and an expert on the Clean Air Act, which regulates the emission of several criteria pollutants, including fine particulate matter. Powell, who was not one of the attorneys on the Balico case, said that even with the most stringent class of air pollution permit that Balico would need to operate, the gas plant would still emit the pollutants.

“Fine particulate matter is deadly,” said Powell. “It’s one of the worst of all the criteria pollutants to be exposed to.”

The Harvard researchers also modeled costs associated with the plant’s increased risk to public health. They found that, if built, Balico’s gas plant could result in upwards of $31 million in additional annual health care costs, increasing to $48 million annually by 2040. Put together, that’s more than $625 million in cumulative health care costs by 2040.

Including the public health costs associated with Balico’s development provided a counterbalance to the estimated revenue and tax benefits in the company’s proposal to the Pittsylvania County Board of Supervisors, said Elizabeth Putfark, an SELC attorney who represented the concerned residents.

“What’s missing, especially when there’s a gas plant involved, are the incredible costs that come along with it, and the health impacts are a big part of that,” said Putfark.

According to Balico’s website, the data centers were estimated to bring the county between $50 million and $184 million in annual tax revenue through the mid-2030s. Behind the scenes, however, the developer requested that the county slash its local tax rates, meaning the actual revenue would have been much lower than what Balico projected.

In a July 18, 2024, letter reviewed by the Daily Yonder, Balico asked Pittsylvania County’s Board of Supervisors to reduce property taxes for data centers. Balico did not respond to the Daily Yonder’s request for comment.

Among residents, Harvard’s health impact report prompted what Wydner called a “paradigm shift” as community members came to terms with how the plant’s eight emissions stacks, each at almost 200 feet tall, would affect their landscape. “Gas plants are not the most gentle neighbors — you really don’t want to be near gas plants over the long haul,” Wydner said.

Cutting corners

As the race to meet surging U.S. power demand accelerates, states like Virginia have taken to luring urban-based developers to rural counties by promising them tax breaks. Typically, the expensive, ultra-powerful computers that fill a data center’s warehouse-sized buildings are taxed as personal property, which can generate significant revenue for the states and communities that host them.

Yet across the Southeast, state-level incentives for developers reduce the tax revenue that data centers generate. Virginia offers tax exemptions for the purchase and use of computer equipment, so long as data centers meet certain requirements for job creation and investment. West Virginia has a similar policy in place, offering low property tax rates that exempt data centers from paying sales tax on much of their computer equipment. In Kentucky, qualified data centers can also avoid paying sales and use tax, which typically applies to personal property that hasn’t faced a sales tax.

Courtesy of Amanda Wydner

Locally, counties can still impose property taxes on data centers, like the Balico development in Pittsylvania County. That’s why Balico’s initial proposal included estimates upward of $100 million in annual tax revenue for the county. But residents said that without significant accompanying job creation — Balico’s proposal included a few hundred permanent positions after construction — the destruction to the land and environment didn’t outweigh the proposed economic benefit.

“Nobody can argue the fact that data centers pay revenue to governance, but they don’t have the job creation attached,” Wydner said.

Another area of regulation where data centers find convenient policies is in air pollution permitting, according to Powell. Under current regulations, there’s a loophole with how data centers report emissions to comply with the EPA’s air quality standards.

While Balico came under scrutiny for its primary source of gas-fired power generation, other data centers — even those powered by renewables — rely on gas or diesel power as a backup. Many data centers have emergency diesel generators to keep computers humming during storm-caused outages or other problems with the grid.

Regardless of how much these diesel-fueled generators turn on, their actual usage rarely has to be included in permitting applications, Powell said. Instead, data centers only need to calculate the emissions associated with running the backup generators for a set number of hours, which often avoids triggering the most severe permitting requirements. As soon as an outage occurs, Powell said, data centers rely on power from all of their backup generators running at once.

“You can easily see how cranking up hundreds of diesel generators could cause violations of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards,” she said.

An underestimated resistance

In Pittsylvania County, residents ultimately rallied around the opposition to Balico. Between January and April 2025, the developer repeatedly failed to answer community concerns about its revised proposal, which kept the 3,500-megawatt power plant but scaled down the number of data centers.

On April 15, Pittsylvania’s local government voted to deny Balico’s rezoning application. It barred the developer from submitting a “substantially similar” proposal until April 2026, effectively rejecting the data center proposal for at least a year. Balico maintains that an eventual data center campus is not completely off the table, even as it pursues other potential projects for the land, which is still zoned for agricultural and rural residential use.

Elizabeth Putfark and fellow SELC attorney Christina Libre attributed their clients’ win to getting in the fight early and at the local level of government. The attorneys also said they think Balico underestimated the resistance they’d face in rural Pittsylvania County. There, opposition to projects like the one Balico proposed does not track neatly along red or blue party lines.

“The inevitable impact of these big power generation facilities, these fossil fuel plants, is that the local air quality will suffer and people’s health will be impacted, and that’s not something any community wants, no matter how they voted,” Putfark said.

For lifelong residents like Kathy Stump, the decision came as a relief.

“Things don’t always have to happen just because they’re proposed,” Stump said. “I mean, everybody has a voice, and we found out that our voices did count this time.”

Source link

Julia Tilton, The Daily Yonder grist.org