Last spring, the EPA made a surprise announcement: President Trump would consider giving some polluters exemptions from a handful of Clean Air Act rules. To get the ball rolling, all it would take was an email from a company making its case. The EPA set up a special inbox to receive these applications, and it gave companies about three weeks at the end of March to submit their requests for presidential exemption. Hundreds of companies wrote in, including coal plants, iron and steel manufacturers, limestone producers, and chemical refiners.

One industry was particularly eager for exemption: medical device sterilizers. About 40 of the roughly 90 device sterilization plants that operate nationwide, along with their trade association, wrote in, arguing they shouldn’t have to comply with an air quality rule limiting how much toxic material they could emit. That’s because these facilities sterilize medical equipment with ethylene oxide, a potent carcinogen that studies have linked to cancers of the breast and lymph nodes.

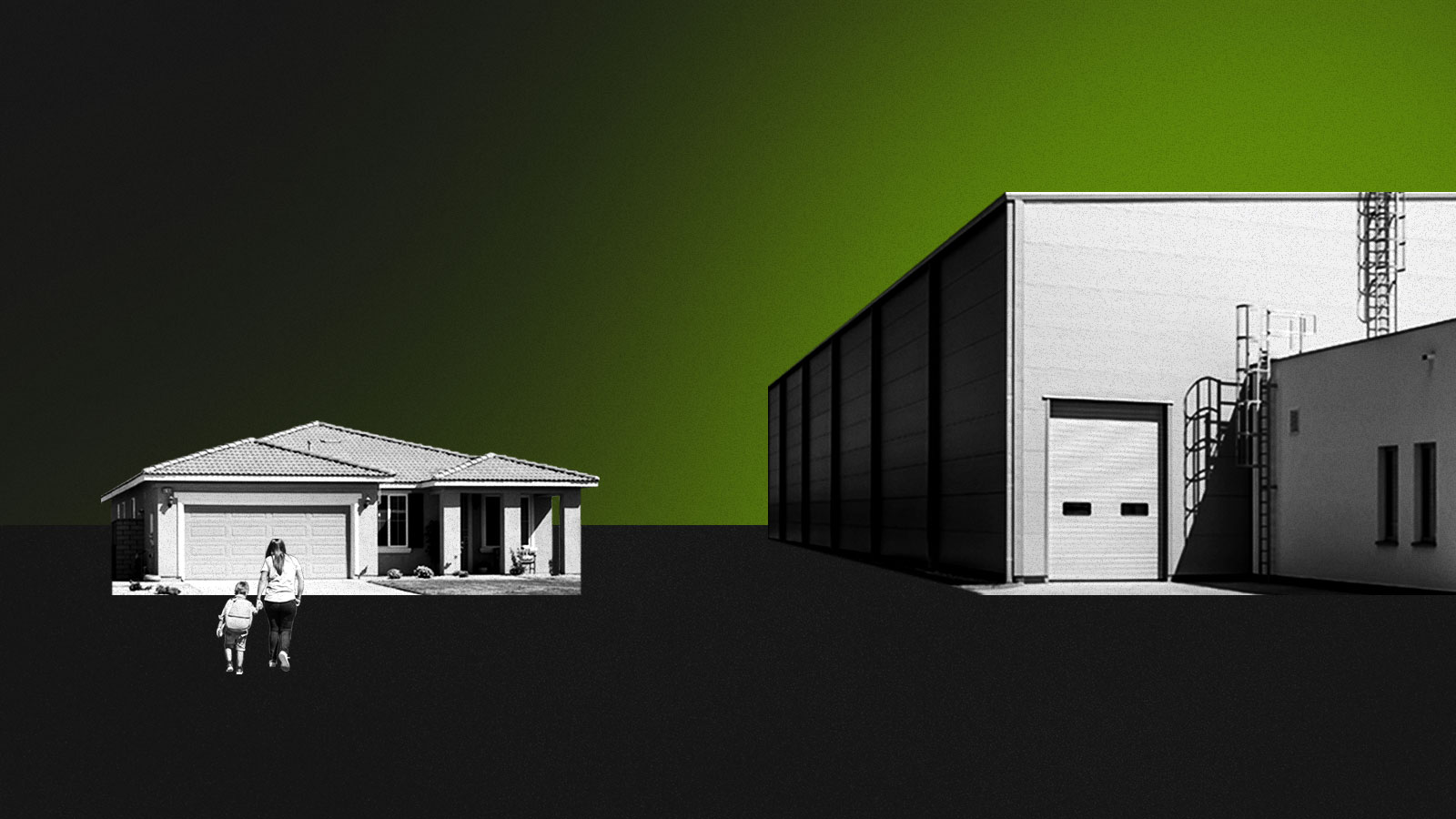

In 2024, the Biden administration issued regulations requiring sterilizers to cut their emissions by about 90 percent. Companies were given two years to comply, and many had begun installing new monitoring equipment and pollution-control devices to meet the standard. But last year, after President Trump took office, the EPA gave these companies a way out; they could request a presidential exemption. About 40 facilities, many of which are located in residential neighborhoods close to schools and day cares, took advantage of the offer and were granted the exemption through a presidential proclamation last summer.

Now, a coalition of national environmental groups and community nonprofits is suing Trump and the EPA, seeking to overturn the ongoing exemptions. Maurice Carter, president of the Georgia-based environmental advocacy group Sustainable Newton, which signed on to the suit, told Grist that financial interests of sterilization companies shouldn’t override public health concerns about ethylene oxide. Any policy change should account for that, he argued.

“You have to do that in ways that are not harmful to the people that live here and to the planet that our children are going to inherit,” he said. Carter lives about a mile away from one of the exempted facilities.

The suit was filed last week in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in Washington, D.C., and assigned to Judge Christopher R. Cooper, an Obama appointee. Trump’s Justice Department, which represents federal agencies in court, has 60 days to respond.

Taylor Rogers, a spokesperson for the White House, told Grist that the president had used “his lawful authority under the Clean Air Act to grant relief for certain commercial sterilization facilities that use ethylene oxide to sterilize critical medical equipment and combat disease transmission.” The Biden-era rule would’ve forced facilities to shut down, Rogers argued, “seriously disrupting the supply of medical equipment and undermining our national security.” A spokesperson for the EPA said the agency doesn’t comment on pending litigation.

A provision in the Clean Air Act does allow the president to grant facilities narrow exemptions from one section of the law. But presidents can only grant an exemption if the technology to meet the standard is not available and the exemption is in the country’s national interest. The sterilization facilities claimed they met both criteria. In a letter to the president, the Ethylene Oxide Sterilization Association, the industry’s trade organization, claimed that companies would not be able to meet the 2024 rule “due to the limited number of equipment manufacturers and workforce shortages.” Supply chain constraints and the time it would take to install and validate equipment meant that the control technology needed “is functionally unavailable within the required timeframes,” the group said.

When the EPA finalized the rule in 2024, it determined that only 7 out of a total of 88 sterilizer facilities “already met the emission standards and will not need to install additional emission controls.” Several others met one or more requirements of the rule. Nearly 30 facilities would be required to install so-called Permanent Total Enclosures, which are among the most expensive pollution control technologies and seal facilities so that ethylene oxide can be trapped and burned.

Georgia has the highest concentration of exempted sterilization plants; all five of the state’s facilities were granted exemptions. By comparison, only two of the facilities in California, which has the largest number of sterilizers in the country, received exemptions. According to records submitted to the state environmental agency, nearly all California facilities already meet the vast majority of requirements laid out in the 2024 rule. One facility in Atlanta met the standards as early as 2022 — yet it nevertheless received an exemption.

“These are facilities that have been making changes to their processes in their facilities to comply, and yet they received exemptions anyway,” said Sarah Buckley, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the environmental groups suing. (Editor’s note: The Natural Resources Defense Council is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.)

“That shows that the president was not making any good faith determination, was not basing this on an actual assessment of the facts on the ground and the capabilities of these facilities, but instead was just looking for excuses essentially to hand out free passes to avoid the rules,” Buckley added, calling the exemptions a “get-out-of-jail-free card.”

James Boylan, head of the Georgia Environmental Protection Division’s air protection branch, said the agency had been working with companies to install upgraded control equipment and revise permits to comply with the 2024 rule before President Trump announced that Georgia’s sterilization facilities would be exempted. Some of those updates have since been delayed because of the exemption, Boylan told Grist in an email.

If companies exceeded the Clean Air Act emission limits and faced state action or lawsuits by community groups, they could use the exemption to claim the rules don’t apply to them. Companies that are exempted will also be relieved of the cost of complying with regulation. The EPA estimated that it would cost $313 million for all of the roughly 90 sterilizers to meet the new standards. But even those already in compliance could benefit from an exemption, because monitoring and pollution control equipment require regular maintenance and oversight.

“There is a monetary incentive to not operate equipment even if you already have it,” said Buckley.

Sterilizers aren’t the only industry benefiting from these exemptions. Last year, President Trump issued a series of proclamations exempting more than 150 facilities, including dozens of coal plants and chemical manufacturers. Environmental groups have sued over several of these exemptions, claiming that Trump had exceeded his statutory authority. Many of these cases are winding their way through the courts.

Source link

Naveena Sadasivam grist.org