1. Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is a chronic disorder characterized by a wide range of symptoms: widespread pain, fatigue, sleep disturbances, including also cognitive dysfunction, anxiety, depression, and emotional difficulties, which are accompanied by an inability to perform usual daily activities. Estimates suggest that this syndrome affects between 2% and 8% of the world’s population, primarily working-age people, and it is significantly more common in women than in men, in a ratio of 3:1 [

1]. The causes of fibromyalgia are still not fully understood; there is no single factor cause of FM, it is rather believed to be a combination of genetic predisposition, immunological and neuroendocrine dysfunctions, and environmental factors, especially psychological or physical stressors, but for now there is no consensus regarding etiopathogenesis, classifications or treatment [

1,

2].

Fibromyalgia is often described as a pain processing disorder in the central nervous system, which makes patients hypersensitive to pain. Elevated levels of certain neurotransmitters, such as glutamate and substance P, may contribute to the sensitization of pain signals. Research shows that fibromyalgia can be associated with a disorder in the functioning of mechanisms like relaxation and stress, as well as with abnormalities in hormonal levels.

Dysfunction of monoaminergic transmission is currently the main observed change in FM, which leads to increased levels of the excitatory neurotransmitters glutamate and substance P and decreased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the spinal cord at the level of descending antinociceptive pathways. In addition to this dysfunction, the dysregulation of dopamine, as well as the altered activity of endogenous opioids, have been observed, which all together explain the central origin of the physiopathology of FM [

2]. Peripheral pain generators have been the subject of researchers as the relevant cause of fibromyalgia in recent times. In this case, patients manifested symptoms such as cognitive impairment, chronic fatigue, sleep disturbance, intestinal irritability, interstitial cystitis, and mood disorders. Peripheral abnormalities can contribute to an increase in nociceptive tone in the spinal cord, which leads to central sensitization [

3].

Regardless of the abundance of available information, several gaps in the existing literature about FM continue to challenge researchers and clinicians in understanding and managing the condition effectively. These gaps cover diagnostic challenges, limited understanding of pathophysiology, and the role of neuroinflammation. Although FM predominantly affects women, there is also limited research on how the condition manifests and progresses in men. Research on the efficacy of combining pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments is still limited. Furthermore, research often focuses on symptom reduction rather than improvements in the quality of life, functioning, or patient satisfaction.

This review offers a critical and detailed analysis of the diagnosis, heterogeneity of fibromyalgia, evolution of diagnostic criteria since 1990, and treatment of fibromyalgia. Additionally, this review synthesizes various hypotheses regarding the aetiopathogenesis of fibromyalgia and emphasizes challenges placed in front of patients and clinicians in the clinical practice. The highlight here is an individualized, patient-centered approach to care. In everyday clinical practice, the most important conclusion from this paper is…DDD Clinicians need training to recognize the various presentations of FM and address patient concerns about their conditions. They always have to bear in mind that patients who feel validated, listened to, and supported by their clinicians are more likely to adhere to treatment. Dismissive or judgmental attitudes from clinicians can lead to mistrust.

1.1. Pain Mechanisms—Central Sensitization

Aberrant signal processing in the peripheral and central nervous system is the basis of peripheral and central sensitization, both of which maintain chronic pain. Neuroinflammation plays a key role in the development of sensitization and is characterized by the activation of glial cells and the production of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines in the central and peripheral nervous system. Various clinical studies using functional magnetic resonance have confirmed central neuronal changes in nociceptive processes. It was back in 2004 when Gracely et al. [

4] showed that after the same strength of pressure stimulus, patients with FM have greater activation in the areas of the brain that process pain compared to the control group of subjects, primarily in the posterior insula and the secondary somatosensory cortex [

5]. In the same areas of the brain, other studies indicated a change in the level of several key neurotransmitters and modulators, which, depending on the CNS site and receptor, have either inhibitory or excitatory effects [

5,

6]. One of the most important neurotransmitters is Glutamate, which plays a key role in excitatory and sensitizing effects as well as in nociception while expressing some inhibitory effects in descending pain pathways. It is suggested that an optimal glutamate tone is necessary, whereby too little or too much can cause the activation of HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis) [

7].

An increased glutamate level within the insula and posterior cingulate was observed in patients with FM [

8,

9].

There is an important neuropeptide that coexists along with glutamate, substance P, which causes the sensitization of the dorsal horn neurons and is found in the primary nociceptive afferents [

9,

10]

The sensitivity to pain increases alongside the level of SP. Several studies have demonstrated that the concentration of SP in the CSF of patients with FM was significantly elevated in the amounts of two to three times higher than in healthy subjects [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Another crucial, most prevalent inhibitory neurotransmitter involved in FM symptoms is GABA. It amounts to 60% to 70% of all synapses in the central nervous system and is found in high concentrations in all brain regions and spinal cord. Its excess and deficiency may contribute to FM symptoms and play a key role in sensitivity for movement disorders, pain, sleep, mood, and cognition [

11,

12].

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) is also an important and well-known monoamine neurotransmitter, with an important role in many biological and behavioral processes such as the inhibition of pain pathways, mood, cognition, sleep, digestion, wound healing, reproductive activity, and circadian rhythms. In patients with FM, decreased levels of serotonin were observed compared to normal controls and were associated with increased pain sensitivity, fatigue, and depression. This decrease in serotonin may also participate in the development of FM [

15]. Similarly, dopamine (3-hydroxytryptamine) has been found to be involved in the descending inhibitory modulation of pain in the brain, as well as in body movements and coordination, motivation, and rewards. A key role of dopamine in the etiopathogenesis of fibromyalgia is shown in its pain regulating capability. Altered levels of these neurotransmitters may be one of the causes of FM onset. Seo et al. [

16] used [C]-(R)-PK11195, a ligand of positron emission tomography (PET) for a translocator protein (TSLO), expressed by activated microglia or astrocytes, to identify specific brain regions (left and right postcentral gyrus, left precentral primary motor cortex, left superior parietal gyri, left medial frontal, left superior frontal, primary somatosensory cortex, left superior parietal gyri, and left precuneus) exhibiting abnormal neuroinflammation levels in patients with fibromyalgia, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). Elevated neuroinflammation in the primary somatosensory cortex may contribute to central sensitization due to excessive neuroinflammation stimulating nociceptors. Similarly, dysfunction and heightened neuroinflammation in the primary motor cortex may impair the descending pain pathway and result in inadequate pain modulation. Increased neuroinflammation in the left frontal regions appears to play a role in the neuropathology and cognitive impairment observed in FM and CRPS patients. Abnormal neuroinflammation in the left precuneus might be linked to trauma experienced by individuals with these conditions. Notably, their study found that FM patients demonstrated greater neuroinflammation in the precentral and postcentral gyrus compared to CRPS patients and healthy controls [

16].

Decreased cortical thickness has been reported in specific parts of the brain (such as the right superior and right and left middle temporal gyrus, left superior frontal gyrus, right fusiform gyrus, and the left amygdala) in patients who reported symptoms of fibromyalgia compared to healthy subjects. These findings are accompanied by reductions in gray matter volume in the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, and the anterior cingulate cortex [

16,

17].

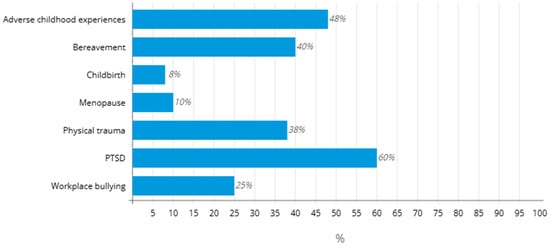

The same study [

16] established a connection between higher levels of affective pain and increased neuroinflammation in the left medial frontal, left superior parietal, and left amygdala regions in FM patients. Given the relationship between elevated stress and PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) with heightened neuroinflammation in FM, psychological trauma and stress are suggested as potential primary drivers of neuroinflammation and pathological symptoms in FM [

16,

18,

19].

1.2. Pain Mechanisms—Peripheral Sensitization

Nociceptors (unmyelinated C fibers and myelinated Aδ fibers) are the primary afferent neurons involved in the detection and encoding of noxious stimuli, transduction of noxious information via cell membranous ion channel (transient receptor potential (TRP), and voltage-gated ion channels) into afferent action potentials, and finally, in the transmission of pain signals to the CNS. TRP channels play a key role in the development of hyperalgesia as they can be sensitized by inflammatory mediators [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Researchers have identified the role of specific TRP channels, such as TRP ankyrin 1 (TRPA1), in the mediation of prolonged hypersensitivity, which makes it a potential therapeutic target in analgesia [

21]. Moreover, they can synthesize and release neuropeptides such as substance P, Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), neurotransmitters, and inflammatory mediators. All these mediators can amplify the local inflammatory response, acting on other ‘silent’ C fibers to lower their activation threshold and increase the excitability of their neurons. This leads to peripheral sensitization [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

The peripheral origin of FM has been of interest to researchers over the past decade. The presence of small fiber neuropathy (SFN—a peripheral polyneuropathy that, like FM, causes chronic widespread pain, exertional intolerance, gastrointestinal symptoms, and chronic headache) has been documented in about half of FM patients by differently designed studies [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Electrophysiologists report excess, spontaneous, and prolonged firing of C and Aδ pain fibers in both adults with FM and SFN, as well as electrical hyperactivity and distal degeneration of the peripheral neurons that mediate pain, heat and cold sensation, and internal autonomic functions [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Considering that skin biopsy is an invasive procedure that, therefore, can only be offered to a limited number of patients with FM, imaging techniques, such as ultrasound (US), could play a role in the diagnosis of SFN.

A study by Di Carlo et al. [

34] investigated in detail the ultrasound (US) abnormalities, expressed in terms of CSA (cross-sectional area) and power Doppler signal, between the nerves of FM patients and healthy controls. Results of the study demonstrated that FM patients tend to show a larger CSA than healthy subjects, and the differences are significant at multiple sites, involving both peripheral and cranial nerves, especially the sural nerve, the sixth cervical nerve root, and the vagus nerve, bilaterally [

34].

3. Diagnostics of Fibromyalgia and Classification Criteria

All previous research on fibromyalgia in more than 30 years has enabled the publication of at least five different classifications and sets of diagnostic criteria for FM. Based on the earliest set of criteria, fibromyalgia was described as a widespread pain condition with a variety of associated symptoms.

In 1990, the American Association of Rheumatologists (ACR) published classification criteria that gave the greatest importance to generalized pain. The same group of authors defined pain in FM as broad and widespread if it is present in the left and right half of the body, above and below the waist, with the presence of pain in the axial skeleton (cervical spine, front chest wall, thoracic and lumbar spine), for a continuous duration of at least 3 months. Clinical confirmation implies the presence of pain in 11 out of 18 sensitive, clearly defined points called tender points as seen in

Figure 2.

A clinical diagnosis of fibromyalgia is made when both criteria are met: the presence of widespread pain that has been continuously present for at least 3 months, with pain on finger pressure in 11 of 18 tender points [

85], and not ‘trigger points”’ as is sometimes commonly used in clinical, everyday practice. Difference between trigger and tender points are shown in

Table 1. The presence of another disease does not exclude the diagnosis of FM.

In order to avoid the subjectivity of the doctor and the patient in making diagnoses, the diagnostic criteria have been revised. Revisions of the classification in 2010 and 2011 reduced the importance and palpability of tender points. In 2016, the American Association of Rheumatology introduced new diagnostic criteria with the aim of minimizing the possibility of misdiagnosis, but their reliability depends on several factors [

88]. The criteria focus on the existence of generalized pain and the presence of comorbidities, especially fatigue and cognitive disorders. To establish a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, the following criteria must be met: WPI (Widespread Pain Index) ≥ 7 i SSS (Symptom Severity Score) ≥ 5 or WPI 4-6 i SSSS ≥ 9, the presence of generalized pain (defined as pain in at least four out of five regions left and right upper region, left and right lower region and axial region, while pain in the jaw, chest, and stomach does not belong to the definition of generalized pain), and that the symptoms have been present for at least 3 months. Moving away from tender point examinations, which were subjective and difficult to standardize, and focusing on the patient’s overall experience of pain and associated symptoms increases the criteria’s reliability. Additionally, using WPI and SSS scales reduces variability in diagnosis. This set of criteria can be used by nonspecialists and does not require the specialized physical examination of tender points, which improves their accessibility. On the other hand, there are some challenges and limitations. First, patients may overestimate, underestimate, or describe their symptoms differently, leading to potential misdiagnosis. Symptoms like fatigue and cognitive issues could lead to an overdiagnosis, especially in patients with depression or anxiety. Failure to rule out other conditions can lead to false positives.

The same criteria underlie the ACTTION (Analgesic, Anesthetic, and Addiction Clinical Trial Translations Innovations Opportunities and Networks—American Pain Society Pain Taxonomy) set of criteria from the year 2018, which singled out sleep disorders and fatigue, but also sensitivity to factors of the external environment: cold, light or noise, sensitivity to touch, in order for criteria to be more practical [

89]. Evolution of diagnostic criteria of FM is presented in

Table 2.

Fibromyalgia lacks specific biomarkers and laboratory tests, making it a diagnosis of exclusion. This can lead to variability between the clinicians. Some patients with FM may not meet strict diagnostic criteria, leading to underdiagnosis and vice versa. Overreliance on self-reported symptoms can lead to overdiagnosis. This is particularly found in cases where other conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus, psychiatric condition) are not correctly ruled out, even with a detailed evaluation of the medical history and the use of additional analyses, tests, and imaging.

Unlike other rheumatic diseases, FM does not manifest itself with visible clinical signs, so a clinical examination will reveal an increased sensitivity to pressure, which patients will describe as pain in certain points or regions of the body. The pain described by patients often resembles neuropathic pain, so 20 to 30% of patients report burning and tingling in the extremities, trunk, or hands. In addition to generalized pain, which is the cardinal symptom of FM, cognitive dysfunctions can also occur, especially ‘fibro fog’, i.e., memory defects, then depression, anxiety, and sleep problems. Patients with FM often complain of symptoms originating from any organ and organ system: headaches, more frequent migraines, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, urgency to urinate in the absence of a urinary infection, dysmenorrhea, stiffness, mostly morning stiffness lasting less than 60 min, and restless leg syndrome.

In identifying a patient who is at risk of developing FM, a number of screening tests have been developed that can be helpful to the physician in clinical work (Fibromyalgia Rapid Screening Tool consisting of six questions, the FibroDetect test [

90], as well as the assessment questionnaires of disease severity and effects of therapy: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) and its modified version (FIQR) [

91], the Fibromyalgia Survey Criteria (FSC), and the Fibromyalgia Assessment Status (FAS) [

92,

93].

4. Therapeutic Approach

Genetic predisposition, personal experiences, emotional-cognitive status, mind-body relationship, and tolerance to stress in their own unique way contribute to the development of fibromyalgia in each patient, which is why this disease is defined as psychosomatic.

The heterogeneity of FM significantly impacts both diagnosis and treatment, as it presents a wide spectrum of symptoms that vary in severity, combinations, and underlying contributing factors. This variability is a challenge for clinicians and requires a holistic, comprehensive, multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach. In summary, a more individualized approach to management. According to the EULAR recommendations (The European League Against Rheumatism) [

94], from 2016, treatment begins with patient education and involves the simultaneous application of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. If there is insufficient effectiveness of one treatment modality, the therapeutic approach should be modified and adapted to the needs of the patient. Primarily, it is essential to emphasize that the heterogeneity of FM means that treatments effective for one patient may be ineffective or even counterproductive for another. Due to differences in pain threshold, psychological factors, and comorbidities, patients may respond differently to the same interventions.

4.1. Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacological treatment should be focused on the type of pain and the mechanism of its occurrence, which is why drugs that have a central action are those that show the highest degree of effectiveness. In addition to reducing pain, medications can alleviate other symptoms that affect the quality of life of patients with FM, such as sleep disorders, fatigue, anxiety, or depression. The most commonly prescribed drugs in the treatment of FM are antidepressants: tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline and nortriptyline), which can be useful in improving the quality of sleep (level of evidence Ia), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as duloxetine and sertraline(Ib)—especially if there are symptoms of depression or anxiety—as well as selective inhibitors uptake of serotonin and noradrenaline (SNRI)(Ia) [

95]. Anticonvulsants (pregabalin and gabapentin) are the drugs whose effect in the treatment of FM has been more extensively investigated, and its efficiency is shown in the

Figure 3. Pregabalin is currently the only anticonvulsant approved by the FDA for the treatment of FM despite many side effects, such as dizziness (Ia) [

95,

96]. Certain therapy, such as opioids and NSAIDs, is not recommended in the treatment of FM due to the risk, lack of efficiency, or concerns about long-term consequences. The only opioid that could be somewhat effective is tramadol, with or without paracetamol [

97,

98].

4.2. Nonpharmacological Therapy

The nonpharmacological approach includes a wide spectrum of alternative and complementary modalities, of which cognitive-behavioral therapy stands out as the most common and most studied type of psychotherapy for patients with FM [

100]. It aims to help patients recognize inadequate patterns of thought and behavior in order to develop effective strategies to deal with stress, pain, and negative emotions that have been shown to lead to the worsening of symptoms. Mindfulness therapy has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of FM and is based on accepting one’s own condition, thoughts, and suffering without judgment. The next important step in the treatment of patients with FM is educating the patient to understand that FM is a real condition, which is functionally disabling but not progressive, and that there is no peripheral tissue damage. Patients should be shown the role they play in their own treatment, familiarized with the benefits of psychotherapy and various relaxation techniques, and clearly pointed out that adaptation to stress and increased resilience are necessary for further treatment. The latest EULAR recommendations are shown in

Table 3. favor exercise therapy because aerobic training, as in the case of other chronic pain conditions, is an important disease-modifying factor. The role of the physiatrist in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia is significant and aims to include patients in an appropriate, individually dosed exercise program. Aerobic training is highly recommended in patients with FM in order to reduce pain and improve psychophysical condition [

101,

102]. Research suggests that acupuncture may help reduce pain and improve function in patients with fibromyalgia and is recommended (albeit weakly) by EULAR due to the moderate quality of evidence in the literature. Hypnosis therapy has become interesting for research in the last few years due to its effect on reducing pain and improving sleep. Tai Chi, Qigong, and Yoga, based on physical movement with adequate breathing and mental relaxation, are promising and safe alternatives to conventional exercise.

There are studies dealing with new approaches in the treatment of fibromyalgia, such as the application of noninvasive brain stimulation techniques, which have been proven to reduce pain in a significant number of fibromyalgia patients. Recent meta-analyses have investigated the efficiency of neuromodulation techniques, particularly of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in the treatment of FM. The meta-analysis by Sun et al. [

103] highlighted that high-frequency rTMS targeting the left primary motor cortex (M1) is particularly effective in reducing pain intensity and improving the quality of life. Their study emphasized the importance of stimulation parameters, including frequency and target area, in achieving optimal outcomes. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Moshfeghinia et al. [

104] evaluated the impact of tDCS on pain intensity in fibromyalgia patients. The analysis, which included 20 studies, revealed that active tDCS significantly reduces pain intensity compared to sham stimulation. The left M1 area was the most common stimulation target, and a 2 mA intensity was frequently used. Findings from two more studies suggest that both rTMS and tDCS are promising noninvasive neuromodulation techniques for managing fibromyalgia symptoms, particularly in reducing pain and improving the quality of life. However, the effectiveness can vary based on stimulation parameters such as frequency, intensity, target area, and session duration. Further research is necessary to establish standardized protocols and to explore the long-term benefits and safety of these interventions [

103,

104,

105,

106].

The patient’s perspective is crucial in managing fibromyalgia, a condition deeply influenced by subjective experiences and multifaceted symptoms. Integrating their fears, beliefs, unique capabilities, and goals into the treatment process fosters trust, improves adherence, and leads to better overall outcomes. By adopting a patient-centered care approach, which requires strong communication and listening skills, empathy, and flexibility to adjust to each patient’s specific needs, healthcare providers can help FM patients achieve not only symptom relief but also a greater sense of control over their condition. Implementation of a multidisciplinary approach often poses some challenges, particularly in low-resource settings. Lack of funding to hire and sustain a multidisciplinary team, limited physical infrastructure, such as space for rehabilitation facilities, and a weak health system. Patients and communities may resist the concept of a team-based approach due to mistrust of the healthcare system or a preference for traditional healing methods. In low-resource settings, the focus is often on addressing acute, life-threatening conditions, leaving little attention to chronic conditions, rehabilitation, and mental health. Future research direction for FM addressing the complexities of this condition and improving diagnostic and treatment approaches. Identifying subtypes of FM could lead to a more personalized approach and improved outcomes, as well as developing specific biomarkers that reflect FM subtypes or undelaying mechanisms. Understanding how genetic variations affect drug metabolism and response could lead to personalized treatment, minimizing side effects. It is necessary to conduct long-term studies to better understand the natural course of FM.

5. Conclusions

Fibromyalgia is a complex chronic pain condition and, as such, requires a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment. Patients suffering from fibromyalgia have a problem with the central processing of pain and struggle with neuropathic pain. Although the exact causes of the disease are unknown, it is believed to be due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Other potential causes of FM may be related to infection, physical trauma, emotional stress, endocrine disorders, as well as immune activation. While the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia is still the topic of researchers, there are no specific biomarkers or laboratory tests, and the diagnosis is clinical.

Newer research, such as certain polymorphisms and gene expression, may indicate a predisposition to fibromyalgia. Modern therapy for fibromyalgia requires multidisciplinary, patient-centered treatment and includes a combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological options. Subjective experiences and the patient’s perspective are crucial in managing fibromyalgia. Their beliefs, fears, trust in treatment, and support from family members are critical factors in determining treatment adherence and the success of therapy. Further research, new knowledge about the mechanism of origin, the discovery of disease biomarkers or FM subtypes, and new treatment modalities are necessary in order to shift from symptom-based therapy to addressing the root causes of FM.