1. Introduction

Today, and in the near future, the key challenge in polymer science is developing alternative methods for polymer synthesis that prioritize renewable feedstocks, while advancing efficient recycling technologies. Due to their remarkably broad range of applications, polyurethanes (PUs) rank among the most widely produced synthetic polymeric materials, with the total production volume projected to reach 29.3 million tons by 2029 [

1]. Chemically, polyurethanes are polymeric carbamates defined by the presence of urethane bonds (-NHCOO), which are formed through a polyaddition reaction between monomers containing two or more hydroxyl groups (diols/polyols) and di- or multifunctional isocyanates. Modifications to diol/polyol backbones can be readily achieved through various chemical methods, enabling the creation of a diverse array of polyurethane materials with a broad spectrum of physicochemical properties that can be finely adjusted. Lupranol polyols, produced by BASF, are an example of a commercial polyol extensively used in the synthesis of polyurethane materials. These polyether polyols are derived from petroleum-based raw materials, primarily propylene oxide and ethylene oxide. The production of other commercial polyether polyols also relies on these oxide intermediates. Similarly, polyester polyols are synthesized from fossil-based feedstocks, such as phthalic anhydride, adipic acid, toluene, and benzene, with the latter two being the key components in aromatic polyester polyols. To address growing environmental and resource sustainability concerns, fossil-derived polyols in PU compositions can be partially or fully replaced by biomass-based polyols, the polyols from vegetable oils (biopolyols), and the polyols from chemical recycling (repolyols). The latter group includes recycled polyethylene terephthalate (e.g., Terol

® by Huntsman) and post-consumer recycled polyols sourced from waste polyurethane foam (e.g., Renuva

TM by Dow). Additionally, CO₂-based polyols (e.g., Cardyon

® by Covestro) utilize carbon dioxide as a feedstock, offering another innovative pathway toward sustainable polyurethane production [

2,

3,

4,

5].

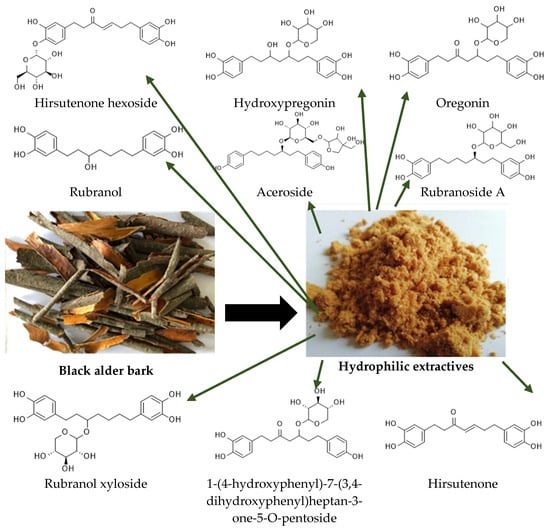

Among the various sources of biomass-based polyols, tree bark—a by-product of the forestry and wood-processing industries—is an abundant and underutilized resource. Different technologies are being developed for the production of bark-derived precursor chemicals for the synthesis of polyurethane materials [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The extraction of bark under appropriate conditions yields bark-based products containing hydroxyl (OH) groups of varying origin. The previous studies have demonstrated that the extraction of black alder (

Alnus glutinosa) bark using fast, energy-efficient microwave-assisted extraction with water at 70–90 °C produces a mixture of polyols dominated by diarylheptanoids. These polyols contain 15.1 mmol·g

−1 of total hydroxyl groups reactive with diphenylmethane diisocyanate, making them suitable for polyurethane (PU) synthesis [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Diarylheptanoids are secondary metabolites found in significant quantities in the bark of various tree species, particularly those belonging to the

Betulaceae family, such as alder trees, which are common in Latvia. These compounds are characterized by two aromatic rings connected by a seven-carbon chain. Typically studied for their biological activities in small-scale applications, these compounds have untapped potential for broader utilization. Our approach is original in its innovative use of black alder (

Alnus glutinosa) diarylheptanoid derivatives as building blocks for the synthesis of bio-based rigid polyurethane foams, leveraging their unique structural properties, such as their richness in aromatic segments; flexible, saturated carbon chains; and the presence of 5–8 phenolic and aliphatic hydroxyl (OH) groups per diarylheptanoid unit [

16]. These features are expected to promote the formation of branched and extensively crosslinked PU networks, resulting in a rigid matrix [

17]. Rigid polyurethane (PUR) foam is highly valued across industries, such as construction, aerospace, and automotive [

18,

19,

20]. The construction sector, in particular, drives significant demand for PUR foam due to its superior thermal insulation properties. Effective insulation helps reduce energy consumption, lower infrastructure costs, and meet sustainability standards. Thermal insulation is a critical global priority, as heating and cooling buildings account for one-third of annual worldwide energy consumption [

21]. With thermal conductivity ranging from 0.025 to 0.046 W·m

−1·K

−1, PUR foam outperforms materials like mineral wool, polystyrene, and cellulose [

22]. Although recent research has prioritized natural insulation materials, such as cellulose, straw, and hemp, these materials are susceptible to moisture and fire, which limits their applicability in certain settings [

23,

24]. In line with the growing emphasis on sustainability within the construction industry, bio-based alternatives to PUR foams derived from renewable resources such as vegetable oils have been developed. While oils like soybean and palm have been widely used, they are often included in human food supply, emphasizing the need for non-edible and abundant alternatives such as tree bark.

This study explores the potential of alder bark-derived diarylheptanoid derivatives with diverse structures as building blocks for polyurethanes (PUs), with a particular focus on rigid polyurethane foams. Among the plant-derived diarylheptanoids, curcumin—commonly found in plants of the

Zingiberaceae family, including

Curcuma longa—is the only compound extensively studied as a component of PU materials. Polyurethanes incorporating curcumin have been synthesized for applications in various fields, including medicine, food packaging, coatings, textiles, and sensors. However, curcumin has not yet been applied in the synthesis of rigid polyurethane foams [

25,

26,

27]. This limitation can be attributed to the relatively low hydroxyl (OH) functionality of curcumin, which contains two aromatic ortho-methoxyphenol groups and an α,β-unsaturated β-diketone group. In this context, oregonin, an alder bark-derived diarylheptanoid xyloside having three aliphatic and four phenolic OH groups, presents a more promising alternative. In our previous studies, it was shown that it can act as a crosslinker for the PU network, and methods for incorporating oregonin-based polyols into polyurethane foams were developed [

10,

11,

12,

15].

This study, for the first time, examines how the structural properties of diarylheptanoids—specifically the presence of sugar moieties and variations in aromatic ring structures (e.g., methoxylated vs. catechol moieties)—influence the mechanical performance and biodegradation behavior of PU materials. Furthermore, it investigates the impact of using alder bark-derived diarylheptanoids as the building blocks for rigid PU foams on their combustion behavior, providing a novel contribution to the field. Combustion behavior, particularly flammability, is a critical factor for the successful application of bio-based polyurethanes in construction, furniture, and transportation, where fire safety is the primary concern [

28,

29].

Recognizing the phenolic hydroxyl groups in the structures of plant-derived diarylheptanoids, their potential as antioxidants was also investigated to enhance the thermo-oxidative resistance of PU materials. Thermo-oxidative resistance is a fundamental property of the PU matrix, determining its stability during long-term exposure to elevated temperatures and influencing its combustion behavior [

30]. Thermal degradation, which occurs via a free-radical chain mechanism, can result from thermal processing or usage conditions. For example, degradation may arise from infrared radiation absorption, typically from solar spectra or nearby heat sources. Thermal and mechanical stresses can facilitate the scission of polymer chains into macroalkyl radicals, initiating the formation of hydroperoxides and subsequent degradation. Various radical scavengers, including hindered phenols, are commonly used to protect PU materials against thermo-oxidation. Low-level volatility is a crucial property of antioxidants for PU systems, as it prevents their loss from the material at elevated temperatures [

31,

32]. Replacing synthetic antioxidants with plant-derived phenolic components aligns with modern bioeconomy trends [

33]. Due to their chemical structures, alder bark-derived diarylheptanoids exhibit a lot of radical-scavenging activity and can compete with commercial antioxidants [

34]. The sugar moieties in diarylheptanoid derivatives, connected to the phenolic part via glycosidic bonds, enable their incorporation into the PU matrix. The reactive aliphatic hydroxyl groups of the sugar units interact with isocyanates, while the less reactive phenolic hydroxyl groups remain available for radical scavenging. Controlling the reactivity of various OH groups of diarylheptanoids in urethane-forming reactions can be achieved by the use of various catalysts [

11]. By chemically bonding the antioxidant to the PU network, its removal during heating is prevented, maintaining its efficiency under high-temperature conditions.

This study aims to evaluate the alder bark-derived diarylheptanoid derivatives as bio-based components for the synthesis of rigid polyurethane (PUR) foams. The objectives include the extraction, chemical modification, and characterization of diarylheptanoid-based polyols, followed by their application in the production of model polyurethane films. Through comparative analyses of the mechanical properties and the durability of polyurethane films derived from diarylheptanoid-based polyols with various structures, the most promising diarylheptanoids were selected for the synthesis of rigid polyurethane foams, which were subsequently subjected to comprehensive characterization. The findings demonstrate that the alder bark diarylheptanoid glucosides containing catechol moieties and aliphatic hydroxyl groups are promising building blocks for increasing the mechanical strength and reducing the flammability of PU foams. Additionally, these compounds were identified as potential technical antioxidants for commercial urethane material production. By exploring the utilization of tree bark-derived diarylheptanoids as biomass-based polyols, this research advances the development of bio-based polyurethanes and underscores the potential of forestry by-products in creating value-added materials for green chemistry and sustainable polymer science.

4. Conclusions

This study underscores the potential of a black alder bark as a renewable and sustainable source of diarylheptanoids, aromatic secondary metabolites that serve as promising multifunctional components for polyurethane (PU) compositions.

The predominant black alder bark diarylheptanoid glucosides featuring catechol moieties connected by a seven-carbon chain, incorporating sugar units, and exhibiting high hydroxyl group functionality have been shown to effectively crosslink PU networks. Moreover, when introduced into a polyurethane matrix, the heptane chain of oregonin can act as a flexible segment, allowing for balance between rigidity and flexibility in the material, thereby improving its performance properties. These unique structural characteristics make diarylheptanoid glucosides advantageous building blocks for producing rigid polyurethane foams. In contrast, the widely studied diarylheptanoid curcumin, with its two aromatic ortho-methoxyphenol moieties and an α,β-unsaturated β-diketone group, offers comparatively limited functionality in PU systems.

The PUR foams incorporating black alder bark diarylheptanoid derivatives, as complete replacements for commercial polyols, exhibited significantly enhanced compression characteristics compared to those of the foams derived solely from fossil-based building blocks. Additionally, these biomass-based polyol-derived-PUR foams demonstrated superior thermal stability, as reflected by reduced weight loss during combustion and greater char retention at elevated temperatures. They also exhibited lower heat release rates, reduced smoke emissions, and extended flame-burning times, making them safer alternatives for applications with stringent fire safety requirements. To prevent the potential negative effects of excessively high functionality in oregonin-based polyols on certain PUR foam properties, particularly increased friability, their functionality can be carefully adjusted during the liquefaction process.

Diarylheptanoid glucosides, particularly those in oregonin-enriched black alder bark extracts, also demonstrated significant potential as natural phenolic antioxidants in PUR foams. During thermo-oxidative aging, their antioxidative effects, evidenced by reduced material darkening, surpassed those of the commercial antioxidant Irganox. This can be explained by the lower-level reactivity of the phenolic groups with isocyanate compared to that of the aliphatic hydroxyl groups, resulting in the partial retention of free phenolic groups in oregonin within the cured polyurethane matrix.

Furthermore, black alder bark diarylheptanoid glucosides, when used as building blocks in PU films, were found to be biodegradable by soil microorganisms. This bio-degradability is attributed to the presence of catechol moieties and the hydrolysis of glucosidic bonds in their structure, which facilitate degradation. In contrast, the aromatic moieties introduced by curcumin into the PU matrix are not biodegradable, highlighting an advantage of alder bark-derived compounds.

To summarize, alder bark represents a versatile, sustainable, and renewable source of diarylheptanoids with broad applicability in polyurethane materials. These compounds enhance mechanical strength, thermal stability, and fire resistance, while offering additional environmental benefits through biodegradability and antioxidative properties. Future research should focus on optimizing diarylheptanoid extraction processes and scaling up their industrial integration, further advancing their potential in eco-friendly polyurethane applications.