3.1. Measuring and Quantifying Fibers

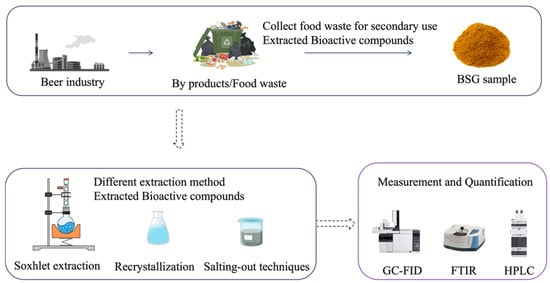

During this investigation, the optimized salting-out fiber extraction [

47] method was used. The extracted materials were analyzed, and the total sample weight was 15,000 mg. The results showed an average residue weight of 13,299 mg, an average protein weight of 11,000 mg, an average Ash weight of 1802 mg, and a blank measurement of 258.5 mg.

Table 1 shows that an extraction rate of 93.3% of total dietary fiber (TDF) was achieved. This is a very similar extraction rate compared to that by Wang et al., who reported that the extraction rate of total dietary fiber from kiwi fruit utilizing an alkaline technique was 92.9% [

48].

Compared with Wang’s group, the BSG in this study had a more loosely bound fiber structure because it was pretreated during the brewing process, which partially degraded the cellulose and lignin structure, making extraction easier [

49].

Furthermore, BSG was particularly rich in water-soluble dietary fiber [

50], which increased solubility during alkaline treatment [

51], resulting in a better extraction yield. In this study, a modest 5% NaOH concentration successfully eliminated non-fiber components (such as lignin) while also stimulating cellulose disintegration and preserving its structure and function.

Although both studies used alkaline treatment, this research applied ultrasound-assisted treatment, which induced cavitation effects to break cell wall structures and accelerate the release and separation of dietary fibers.

Ultrasound-assisted treatment caused cavitation effects, which broke cell wall structures and accelerated fiber release and separation. Furthermore, using 1:1 ethanol for precipitation effectively isolated high-purity dietary fiber, reduced interference from other components, and resulted in a larger extraction yield.

Furthermore, it was important to analyze what kind of fiber had been extracted. Garside et al. reported that FTIR could be used to analyze the chemical composition of fibers [

52], which was similar to Collins et al., who showed that FTIR could measure the variation in the chemical composition of fibers in wheat straw [

53].

The obtained FTIR and BSG extract spectra are shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 2.

Table 2 provides the chemical groups in fibers that were examined. Peaks at 1030 cm

−1 and 1160 cm

−1 represent hemicellulose’s C-O-C stretching vibration and C-O-O stretching vibration [

54]. The peak at 1723 cm

−1 is attributed to a hemicellulose acetyl or uronic ester group [

55]. In plant cell walls, hemicellulose is an amorphous structure that is usually present along with fibers. Xylan, polygalactias glucomannans, poly arabino galactose, glucomannan, and poly-glucomannan are among the common polysaccharides that make up hemicellulose. Hemicellulose is easily impacted by acid or alkali to undergo auto-hydrolysis because of its non-crystal structure and weak bond node connections. The group C-O-C, formed following lipidation or etherification, is the signal produced by the ether bond upon the vibration of glycoside. C-O-C is the glycoside’s primary characteristic peak, and sugar is the main component of the fiber. Etherified hemi fibers are manufactured in the industry to provide biodegradable hydrophobic materials [

56]. Etherified hemi fibers in the food industry has enormous potential as environmentally friendly packaging to preserve food shelf life [

57,

58]. The peak at 1380 cm

−1 represents CH

3 and CH deformation [

59]. It is assumed that the extracted fibers are macromolecular fibers with strong flexibility, generally good elasticity, and easy deformation. The structure is not easily packed well, based on the distinctive detection peaks of CH

3 and CH deformation [

60]. In food science, previous studies point to macromolecular fiber for its lipid-lowering potential [

61].

The N-H bending vibration of amide II and the C=O stretching vibration of amide I, respectively, peaked at 1540 cm

−1 and 1657 cm

−1. Protein backbone vibrational bands are also provided by amide II, which is primarily driven by in-plane N-H bending. The amide I band, which primarily investigates stretching vibrations of the C=O bonds in the peptide backbone, is the most efficient and often employed band in the research of protein secondary structures [

62]. However, the chemicals are speculated to be too strong to disrupt the secondary structure of the protein upon extraction since the C-N stretch bending was not found [

63]. This proved that the protein structure was damaged and not fully extracted. Furthermore, any remaining protein had a negative effect on the angle at which the fibers were extracted and interfered with future quantification studies of the fibers. Peak 2700 cm

−1 was attributed to bending OH vibrations for tannins [

64]. Both tannins and tannic acid are polyphenolic compounds capable of forming extremely complex chemical structures, which made it challenging to interpret the map. However, the stretched area (3000 to 2700 cm

−1) of the primary functional groups of tannins, according to prior research, primarily provided information about the spatial arrangement and interactions of hydroxyl substituents, furthering our understanding of critical diagnostic factors for tannins. Peak 3290 cm

−1 represents the vibration of the OH group of cellulose [

65], while peak 2853 cm

−1 represents the asymmetric and symmetric CH

2 and CH

3 of epoxy resin [

66].

According to FTIR peaks (

Figure 2), there are numerous compounds of hemicellulose, lignin, and cellulose. The characteristics of these chemical groups, such as hemicellulose biodegradability, macromolecular fiber elasticity, lipid degradation potential, and cellulose’s stable structure, make them suitable for use in sustainable food packaging and functional food development. These chemicals not only extend the shelf life of food but also improve its nutritional content, creating a circular economy by providing innovative solutions that merge food science with environmentally friendly materials.

Therefore, hemicellulose, lignin, and cellulose are the three main types of fibers extracted in this study. Based on these three fibers—hemicellulose, lignin, and cellulose—further quantification was conducted.

Previous studies reported that hemicellulose, lignin, and cellulose were quantified using HPLC [

67,

68,

69]. It was mentioned that the sample weighed 15,000 mg. The qualitative phytochemical profiling of the hemicellulose, lignin, and cellulose present in the BSG extracts, along with their peak area percentage and molecular formula, is provided in

Table 3.

The top three significant compounds were hemicellulose (8245.2 mg/L), lignin (10,432.4 mg/L), and cellulose (13,245.4 mg/L). The extraction rates were 54.9%, 69.5%, and 88.3%, respectively.

Table 4 shows that Pal et al. used NH

3 in a water-THF solvent to remove lignin from rice straw, achieving a removal rate of 60% [

70]. A 65.81% recovery rate was reported for lignin extraction from bamboo using optimized ultrasound-assisted extraction [

71]. Compared with this study, which achieved a lignin extraction rate of 69.5%, the results of other studies were significantly lower. The extraction rate of hemicellulose in this study was 54.9%, and the extraction rate for cellulose was 88.3%, compared with a 32.57% hemicellulose removal rate and an 81.2% cellulose removal rate from bagasse using hydrothermal pretreatment [

72]. It was clear that this study achieved a higher extraction yield.

The variances could be attributed to multiple factors, such as extraction methods, extraction duration, fiber source, or material variations. However, the results of this study showed that the method applied was simpler and capable of obtaining large amounts of cellulose, making it a suitable reference for factory applications.

3.2. Quantification of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidants

Numerous scholarly studies in the field of extracted phenolic compounds and antioxidant analysis from agricultural waste have delved into the complex challenges of isolating these compounds while carefully avoiding the unintended introduction of pollutants [

73,

74].

The total phenolic content was quantified using a Phenolic Compounds Assay Kit, and the results showed 64 mg/L. Antioxidant results showed 24 mg/L using an Antioxidant Assay Kit. The extraction rates were 0.52% and 0.24% for phenolic compounds and antioxidants, respectively.

It is evident that the extraction rates of total phenolic compounds and total antioxidants are relatively low.

The low extraction yields could be attributed to limitations in the recrystallization extraction method [

75,

76]. Chemicals used in the process might have led to the natural degradation of the target compounds during extraction. Additionally, based on the HPLC chromatogram, the noise levels were relatively low, and fewer unknown peaks appeared compared to the GC-FID results. This indicates that the purity of the extracted compounds in the HPLC analysis is likely higher. The lower noise and fewer unidentified signals in the HPLC chromatogram suggest that the extraction and purification steps might have been more effectively performed. However, some researchers suggest the use of ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) [

77], which reduces solvent usage, is environmentally friendly, and increases productivity.

Similarly, previous studies often employed the strategy of selecting chemicals for solid extraction according to the particular compound being examined [

78,

79]. The qualitative phytochemical profiling of the bioactive compounds present in the BSG extracts, including their peak area percentage and molecular formula, is presented in

Figure 3. Based on abundance, the top four significant compounds are oleanolic acid (0.243 mg/L), oleic acid (0.057 mg/L), linoleic acid (0.547 mg/L), and arachidic acid (0.1737 mg/L) in

Table 5.

The goal was to extract linoleic acid and oleanolic acid from BSG samples through Soxhlet extraction, which aligns with the objectives of analogous studies conducted by Al et al. and Rahim et al. [

80,

81]. The selection of n-hexane, diethyl ether, and formic acid for extracting linoleic acid and oleanolic acid closely reflects established conventions in the field [

82,

83]. In line with the varying levels of linoleic acid and oleanolic acid in BSG, as evidenced by numerous prior studies [

84], Ruiz-Ruiz et al. extracted oleanolic acid (0.0244 mg/L) by solid–liquid extraction [

85]. The extraction results of this study show a significantly higher concentration of oleanolic acid than the value reported by Ruiz-Ruiz et al.

Compared to previous studies, Ruiz-Ruiz et al. reported an oleanolic acid yield of 0.0244 (mg/L) using solid–liquid extraction, which is significantly lower than the yield obtained in this study.

The differences could be due to various factors, including the extraction methods, the duration of extraction of the source of linoleic acid, or variations in the materials used. In line with prior research efforts [

29,

86], the possible constraints associated with conventionally extracted products are acknowledged.

Soxhlet extraction is highly effective in isolating lipid-based compounds; however, it does not efficiently break down cell wall structures, which can limit the release of bound phenolic acids and antioxidants. Since the extraction process must preserve the integrity of bioactive compounds while enhancing yield, alternative methods should be considered.

On the other hand, the top six key compounds were ascorbic acid (1.5923 mg/L), gallic acid (2.314 mg/L), catechol (2.739 mg/L), ellagic acid (162.88 mg/L), acetylsalicylic acid (0.63 mg/L), and vanillin (590.1688 mg/L). The 45.8% extraction rate of vanillin, as shown in

Figure 4 and

Table 6, displays a few unknown peaks that will need further investigation.

Vanillin plays an important function in the food sector by increasing the sensory appeal of baked goods, ice cream, and beverages [

87]. It is important to point out that customers have recently sought “natural food additives” [

88]. Consequently, the successful extraction of vanillin in this study has practical applications.

The chromatographic analysis, consistent with previous studies [

89], revealed a range of compounds, including those exhibiting different polarities, aligning with the established knowledge within the field [

40].

The qualitative analysis of phytochemicals, as depicted in

Table 6, aligns with previous research by Wang [

90] as well as Sun et al. [

91]. These results emphasize the existence of important bioactive compounds within BSG extracts. The detection of vanillin and ellagic acid as the primary compounds aligns with the findings of other researchers in this field [

92]. The selection of ethanol and methanol as solvents for extracting vanillin and ellagic acid reflects established conventions in the field [

93,

94].

Regarding the fluctuations in the levels of vanillin and ellagic acid within BSG, as reported in several preceding investigations, Lopes et al. extracted vanillin 109.2 (mg/L) by solvent extraction [

95], while Bonifacio-Lopes et al. extracted vanillin 27.80 ± 0.49 (mg/L) by ohmic extracts [

96].

The results of our study demonstrate a considerably higher concentration of vanillin compared to the other two studies. Specifically, our extraction yielded a concentration more than 5 times higher than the value reported by Lopes et al. and over 20 times higher than the value from Bonifacio-Lopes et al. These variations could be attributed to differences in the extraction methods, the source of the vanillin, or variations in the experimental conditions between the studies.

However, it is regrettable that within the existing body of research, there is a notable lack of studies that have identified ellagic acid as a primary target compound in the context of BSG. It is important to note that BSG is primarily used as animal feed, compost, or for other agricultural purposes, and not typically as a source of ellagic acid extraction [

97].

In accordance with the discoveries made by earlier investigators [

98,

99], our study recognizes the potential limitations linked to traditionally extracted products. Therefore, the aims of this study were to investigate alternative extraction methods in upcoming experiments.

This study also aimed to explore more efficient alternative extraction techniques to enhance yield and product quality. Additionally, beyond improving extraction methods, industrial scalability is also a crucial consideration, particularly in overcoming challenges related to cost and environmental impact.

Scaling up the process presents challenges, such as increased solvent usage, leading to higher costs and environmental risks. Solvent recovery systems can help mitigate these issues to some extent. Soxhlet extraction proved to be inefficient, so countercurrent extraction was adopted to improve efficiency. Although these methods may increase costs, semi-continuous or automated systems can enhance overall process efficiency.