1. Introduction

Attending to the emotional connotations expressed in human voices is something we do on a daily basis. Whether an angry outburst in busy traffic, the gentle expression of affection by a loved one, or the scream of an unfortunate protagonist in our favorite horror movie, emotional vocalizations are all around us. They form an essential basis for social interactions, providing information about the emotional states of others, and are vital for adequate and prompt responses such as empathy, caution, or even fight-or-flight responses [

1].

In an effort to increase our understanding of vocal emotion processing, researchers used electroencephalography (EEG) to investigate the corresponding neuro-temporal dynamics in the brain. This cumulative work revealed a discrete time-course comprising a series of hierarchical sub-processes, which may be linked to distinct electrophysiological components [

1,

2] or time windows of neural processing [

3]. The first stage consists of basic sensory processing of the auditory input and is assumed to be reflected in a negative ERP component emerging shortly after stimulus onset, the N100 [

1,

4]. In the second stage, these cues are evaluated for emotional meaning and integrated with further emotional processing, which has been thought to manifest in modulations of subsequent responses, including the P200 component [

5] and the mismatch negativity (MMN) [

6]. Finally, in the third stage, this information is relayed to higher-order cognition, such as semantic processing or evaluative judgements like emotion appraisal [

7], and to response preparation. In the EEG time-course, these processes have been linked to the N400 component [

8], the late positive potential (LPP) [

5], and the (lateralized) readiness potential [

9], respectively.

Discernable in the first stage, a crucial aspect of vocal emotion perception lies in the processing of acoustic markers, such as the fundamental frequency (F0) and timbre (put simply, any perceivable difference in voice quality between two voices that have identical F0, intensity, and temporal structure), and how their specific profiles vary in different emotions [

2,

10,

11,

12]. However, how the human brain precisely extracts emotional meaning from the acoustic input remains insufficiently understood [

2]. Nussbaum et al. [

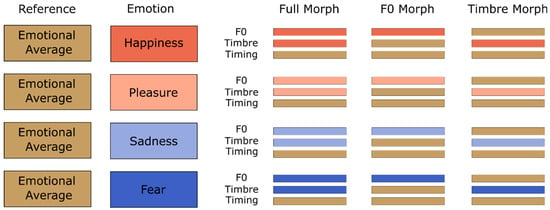

13] targeted this research gap by exploring how the processing of F0 and timbre links to the aforementioned ERP components. They employed a parameter-specific voice morphing approach to create stimuli which contain emotional information in F0 or timbre only, while other parameters were kept emotionally non-informative. Their experiment not only revealed behavioral effects, but also modulations of the P200 and N400 by these vocal cues, reflecting their relative importance for discerning specific emotions: while F0 was found to be relatively more important for the perception of happiness, sadness, and fear in voices, timbre was found to be more relevant for the perception of pleasure.

A notable phenomenon described in the literature regards the profound inter-individual differences in vocal emotion perception [

2,

8,

14,

15]. A relevant trait in this context is musicality [

16]. The interconnection between musical expertise and vocal emotion perception has been shown on a behavioral level, with musicians being significantly more accurate in discriminating between vocal emotions than non-musicians [

16,

17,

18,

19]. A recent behavioral study suggests that this advantage is based on increased auditory sensitivity, specifically towards the pitch contour of the voice, characterized by the fundamental frequency (F0), rather than towards timbre [

20]. It is, however, impossible to discern the functional and neural locus of this increased sensitivity from the behavioral response alone. Specifically, the degree to which differences linked to musicality originate from early representations of acoustic information or from later, more controlled aspects of emotional processing and decision making remains unclear.

To address this, Nussbaum et al. [

21] recorded the EEG of substantial samples of musicians and non-musicians. As in their previous study [

13], Nussbaum et al. presented vocal stimuli manipulated with parameter-specific voice morphing, with emotional content expressed in F0 or timbre only. They found that the P200 and even later N400 component did not differ significantly between groups regardless of any acoustic manipulation. Instead, group differences were observed for a later (>500 ms), central–parietal LPP. While non-musicians displayed similar reductions in the LPP in response to acoustic manipulation, musicians showed an emotion-specific pattern: For negative emotions, such as fear and sadness, musicians’ LPP was unaffected by the acoustic manipulation, suggesting that musicians were well able to compensate for a missing parameter. For happiness and pleasure, however, the LPP was reduced to a larger extent when F0 (as compared to timbre) was rendered uninformative, potentially supporting the special reliance on F0 cues reported in the behavioral data. The authors conceded that the observation of differences in later time windows only was unexpected and discussed potential explanations. On the one hand, this finding could indicate that musicians’ higher auditory sensitivity is reflected in the more efficient higher-order integration of acoustic information rather than a facilitation of early bottom-up analysis processes. On the other hand, earlier (<500 ms) group differences in neural processing cannot be ruled out from these data because scalp-recorded ERPs can be relatively blind to a subset of combinations of deep neural generators, because a conventional ERP analysis might simply lack the statistical power needed to uncover these effects in their data, or both.

Consequently, Nussbaum et al. [

21] suggest using additional analysis methods, such as machine learning-based multivariate pattern analyses (MVPAs). MVPA is a computational method used to analyze complex neural data by identifying patterns of brain activity across multiple variables, such as channels or timepoints in the EEG [

22], or voxels in brain imaging data [

23]. Unlike univariate approaches, which focus on individual brain regions or signals, MVPA evaluates the distributed nature of neural representations, making it particularly useful for decoding cognitive states, predicting behaviors, or tracing sensory perception [

24]. For instance, in recent years, MVPA has gained popularity in the field of visual cognition (e.g., [

25,

26,

27]), where the goal is to understand how patterns of neural activity correspond to specific perceptual states or processes. MVPA has been shown to have an increased sensitivity towards small effects [

22,

28]. In addition, it allows for better consideration of the continuous nature of cognitive processes as the EEG data are analyzed in an unconstrained manner [

29] in contrast to a component-focused conventional ERP analysis [

22,

30]. There are indeed examples where an additional MVPA could uncover early EEG effects, which a conventional ERP analysis failed to discover (e.g., [

31]).

To this end, the aim of the present study was to re-analyze the data obtained by Nussbaum et al. [

21] using a time-series multivariate decoding approach. We used their EEG dataset of musicians and non-musicians on vocal emotion perception to train a linear discriminant classifier (LDA) to discriminate between the four presented emotional categories (happiness, sadness, fear, and pleasure). This approach allows for the representation of emotion to be finely traced throughout the processing time-course with the goal of providing a more detailed picture of the relationship between musicality and vocal emotion processing. Based on the findings obtained by Nussbaum et al. [

21], we expected significant decoding in later parts of the epoch (>500 ms) but were also interested in whether this exploratory approach would reveal additional early decoding effects (<500 ms).

4. Discussion

The neural correlates of individual differences in emotion recognition ability are a pivotal area of ongoing research [

46]. The aim of this study was to investigate the neural differences in vocal emotion perception of musicians and non-musicians, considering that musicality could be one of the determinants of individual differences in vocal emotion perception [

20]. To this end, we performed a re-analysis of EEG data first reported by Nussbaum et al. [

21] with a neural decoding approach. Together with this previous paper, a distinctive feature of the present study is that it allows a direct comparison of neural decoding and ERP data from the same experiment.

Overall, we succeeded in decoding representations of vocal emotions from the EEG. We observed significant and robust decoding beginning at 400 ms after stimulus onset for decoding on all trials and across groups. When comparing musicians with non-musicians, there was significant emotion decoding on data from musicians starting from 500 ms to the end of the epoch, which contrasted with very few significant timepoints at best on the data from non-musicians. Furthermore, when looking at classification based on F0-morphed stimuli, the same pattern persists, with significant decoding emerging for musicians but not for non-musicians. Thus, for Full- and F0-Morphs, it seems that the emotions participants listened to can be somewhat extracted from the musicians’ EEG responses, but not from the responses of non-musicians. For the classification of timbre-morphed stimuli, however, no substantial EEG decoding of vocal emotions could be discerned in either group. Most importantly—and in line with the previous ERP analysis—there were no significant effects before 500 ms, even with a more sensitive decoding analysis.

In general, these results suggest that the EEG of musicians contains more traceable information about the emotional categories than that of non-musicians [

24] and that this mainly manifests in later stages of the processing stream. This converges with the previous ERP findings, which only discovered group differences in the LPP component between 500 and 1000 ms and not earlier. In addition, our results also highlight the importance of F0 as most of the emotional information in the musicians’ EEG seems to be contained in the fundamental frequency. This is in line with the previous literature [

47,

48], specifically recent behavioral evidence, where musicians exhibited an advantage in perceiving emotions expressed via F0 only [

20] compared to emotions expressed via timbre. Within that study, the behavioral classification of Timbre-Morphs was also closest to the guessing rate, which could explain why no decoding emerged for Timbre-Morphs in our analysis.

As discussed by Nussbaum et al. [

21], it may seem surprising that group differences appeared no earlier than 500 ms, as one could have expected to find differences in early acoustic-driven processes. However, the EEG data suggest that the differences in the auditory sensitivity towards emotions are primarily reflected in later, more top-down-regulated complex processes such as emotional appraisal [

2,

7]. One may speculate that musicians do not differ from non-musicians in the extraction of F0 information during early auditory processing but may be more efficient in using the extracted F0 information for emotional evaluation and conscious decision making. Thus, the absence of early differences between groups is not a result of a lack in statistical power but reveals that musicality indeed shapes later stages of emotional processing. In the same vein, one might be tempted to argue that the timing effects of the stimuli could have influenced the present results. For instance, a late decoding effect for musicians could either mean that neural decoding indeed took considerable time to occur, that emotional information became available only later in the stimuli and triggered an early brain response, which was therefore visible in later EEG activity, or anything in between these extreme alternatives. However, the fact that other work found early ERP differences between emotions with the present stimuli [

13] is more consistent with the present interpretation that, even though emotional information is available early in the stimuli, neural decoding for musicians emerges in later processing stages. Additionally, potential confounds related to varying stimulus durations and offsets can be ruled out as the timing parameter was consistently taken from the emotional average during the morphing process (

Figure 1). While individual stimuli may have varied slightly in the duration between pseudowords and speakers, the timing parameter was kept consistent across emotions.

This study presents a remarkable convergence of findings across different analyses of EEG data. In both the ERP and the decoding approach, differences were found >500 ms. However, in the ERP analysis, group effects were only observed for some of the emotions, namely happiness and pleasure. The present decoding approach provides a more holistic picture as it returns classification success across all emotions. Thus, our findings highlight the added value of analyzing the same EEG data using different methods as they help us understand how the idiosyncrasies of different methods shape the inferences we make from the data.

Despite these intriguing findings, we must consider several limitations of this study. Even when statistically robust, the observed above-chance decoding accuracies are low, suggesting that the observed effects are relatively small. This could be related to several potential reasons: First, as this study presents an exploratory re-analysis, it was not originally designed for a neural decoding analysis. As a consequence, the number of trials is not ideal and lower than that in studies with similar approaches from the visual domain (e.g., [

43,

49,

50,

51]), which will likely have impacted classification performance. Second, we used a linear classification algorithm to decode the emotional representations, which can have lower performance than non-linear deep learning approaches, for example [

52]. As deep learning algorithms require large amounts of training data for robust classification [

53], we considered a more traditional machine learning application to be the better choice for our dataset. Even so, for neuroscientific decoding studies interested in the representations of cognition and not prediction, such as in brain–computer-interface (BCI) applications [

54,

55], the focus lies more on the fact that information patterns are indeed

present in the data. With this in mind, even low decoding accuracies provide useful insights if they are statistically robust and thus generalize across the population [

24].

Finally, the question might arise whether the modulatory role of musicality on vocal emotion perception could be further qualified by individual differences in hormonal status, especially in women during the menstrual cycle. There is some evidence that people adapt their voice depending on vocal characteristics of an interaction partner and that these changes are modulated by the menstrual cycle phase in women [

56]. It has also been proposed that some musical skills might reflect qualities that are relevant in the context of mate choice, and thus, that women might be expected to show an enhanced preference for acoustically complex music when they are most fertile. Unfortunately, this hypothesis was not confirmed upon testing [

57]. Although future research in the field of the present study might delve into a possible role of more fine-grained aspects of individual differences (such as hormonal status), generating specific hypotheses about how hormonal influences could qualify the present results seems difficult at present.

Consequently, despite these limitations, these results give valuable insights into how vocal emotions are represented in the brain activities of musicians and non-musicians. They also highlight the general potential of neural decoding approaches in researching nonverbal aspects of voice perception and emotion perception from the human voice in particular. In recent years, these methods have become more and more popular with works in the visual domain, but only a few studies have employed EEG decoding to investigate auditory perception. These have mainly focused on decoding speech content [

58,

59] but less on how the brain processes auditory nonverbal information about speakers, such as emotional states. Giordano et al. [

60] studied nonverbal emotional exclamations by decoding emotional information from time-series brain activity related to synthesized vocal bursts. In a recent study, musical and auditory emotions were identified from the EEG activity of cochlear implant users [

61]; however, their focus was more on reaching high prediction accuracies from single-electrode recordings rather than tracking the time-specific correlates of the perception process itself. Thus, to our knowledge, this study is among the first to investigate the neuro-temporal correlates of individual differences in vocal emotion perception with a neural decoding approach with a direct comparison to standard ERP findings. While the advantages of MVPA over the traditional ERP method are increasingly recognized in visual perception research [

29], its application in the auditory domain remains relatively underexplored. We anticipate that future studies within this field could greatly benefit from this method since the effects of musicality have been especially conflicting and hard to uncover [

16,

17,

21]. The potential of the method to uncover the decoding of other acoustic parameters of emotions should also be further investigated, especially with regard to time-sensitive cues [

3].