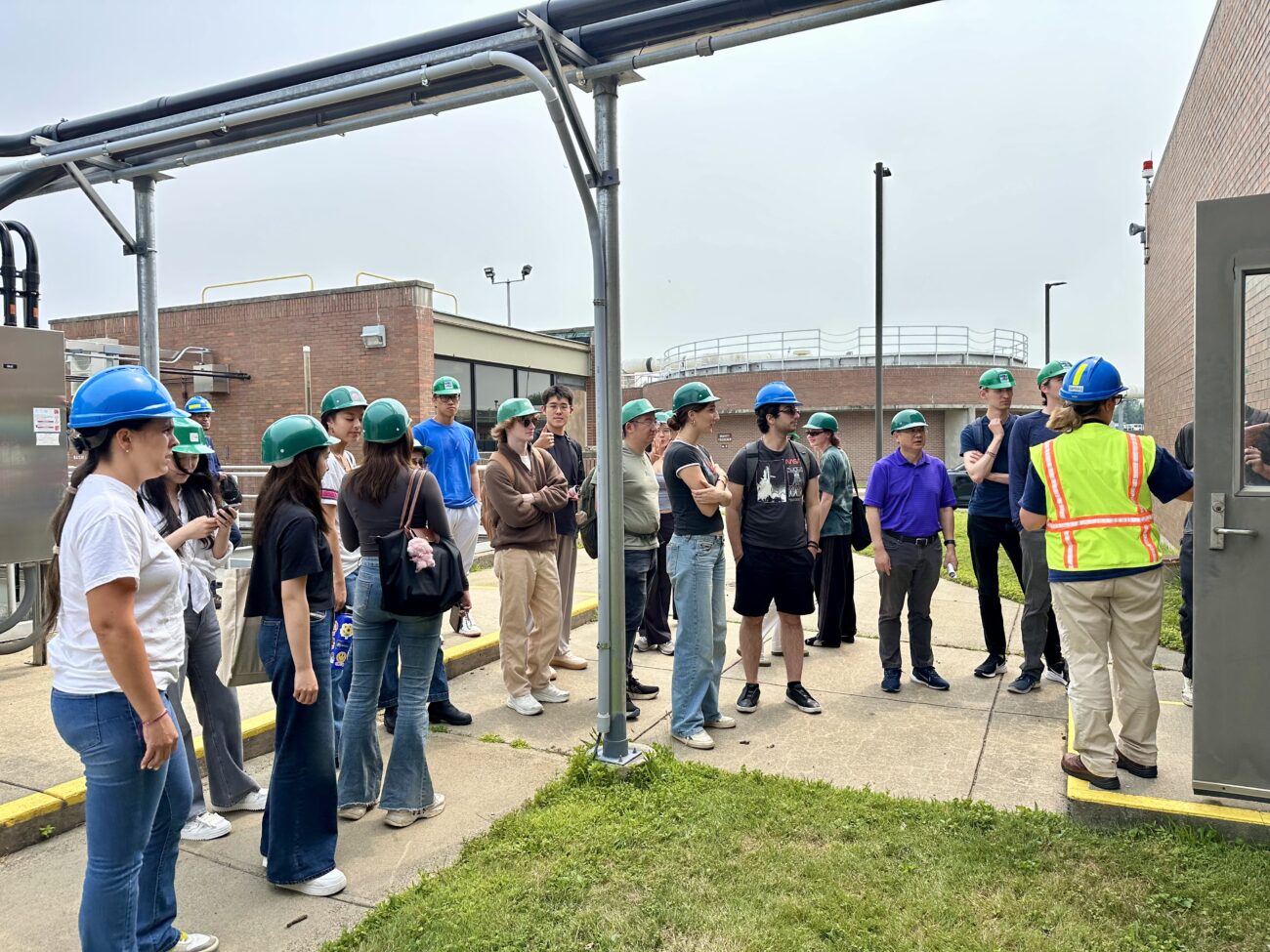

At the end of the summer term, students from Columbia University’s MPA in Environmental Science and Policy program visited Stamford, Connecticut’s Water Pollution Control Authority and its municipal recycling operations. At first glance, these facilities represent the kind of critical, behind-the-scenes infrastructure that most of us take for granted: wastewater treatment plants that protect public health and ecosystems, and recycling/composting efforts that aim to reduce what ends up in landfills. Yet, as future policymakers, water and waste managers, and advocates, we left with as many questions as answers.

Wastewater: Essential but fragile

One of Stamford’s notable achievements is its separate sewage and stormwater system, which reduces flooding risk and helps maintain cleaner waterways. The facility also draws part of its energy from solar power, a step toward sustainability.

As student Brendan Chapko observed during the visit, Stamford’s team has chosen to move away from chlorine and adopt UV disinfection.

“They decided to switch from chlorine to UV, making the water leaving the plant even cleaner than necessary, protecting the other equipment and helping ensure that what flows into Long Island Sound is as safe as possible,” he explained.

Advanced nitrogen removal: Innovation with impact

One highlight of Stamford’s plant is its advanced nitrogen removal system, which not only improves the water quality of the Long Island Sound but also participates in Connecticut’s nitrogen credit exchange program. This statewide initiative allows municipalities to buy and sell nitrogen credits, rewarding plants that reduce nitrogen discharges below their allocation.

In 2018, Stamford earned a performance score of 633 nitrogen reduction credits in Connecticut’s Nitrogen Credit Exchange Program. With the statewide credit value set at $11.02 that year, Stamford received a total payout of $2.5 million, funds that can be reinvested in treatment upgrades, system improvements or community initiatives.

It is worth asking: Could nitrogen credit trading models be scaled or adapted elsewhere as a way to both incentivize environmental performance and create sustainable financing for infrastructure?

Recycling and composting: Aspirations and contradictions

Stamford stands out as one of the few towns in Connecticut with a functional, citywide recycling and composting program, often cited as a local leader in this area. The city offers public food scrap drop-off sites, along with seasonal composting initiatives for leaves and Christmas trees—initiatives that reflect an encouraging commitment to waste diversion.

Yet even leadership comes with challenges. Much of Stamford’s trash still travels hundreds of miles to landfills in Pennsylvania, as recycling often costs more than disposal. This economic imbalance undermines the long-term viability of circular economy solutions. The city once explored a waste-to-energy project, but it did not move forward. While such facilities can reduce landfill dependence, they are not truly circular, since they destroy materials instead of keeping them in productive use.

The composting program also has clear limitations. A state law requires composting in schools, but it applies to only five of the largest schools in Connecticut. Food scraps at the Stamford facility are dehydrated to reduce volume and rodent risk, but concerns remain about microplastic contamination, stemming not only from mixed waste but also from the composting process and temperature conditions used.

It also seemed there was less emphasis on prevention, such as reducing food waste before it is generated. In a country where household food waste is particularly high, prevention could be the most transformative—and cost-effective—strategy. Shouldn’t prevention be the core of any sustainable food waste program?

Here, too, open questions remain: For example, Should Connecticut invest in regionalized composting and waste solutions to achieve economies of scale? How can municipalities more actively engage the private sector, which generates significant waste and could help drive innovation? And perhaps most urgently: How can we make prevention, not just management, the centerpiece of future strategies?

Tradeoffs and transitions

The facility’s efforts to adopt renewable energy and ban plastic bags are positive steps. But here we must be precise: the plastic bag ban’s primary value in this context is operational, preventing bags from clogging wastewater systems and limiting their breakdown into microplastics in compost. Wipes and other single-use products, however, continue to strain the system, and they will keep doing so until the root problem, awareness and education, is directly addressed.

These questions bring a more uncomfortable truth to light: In sustainability, complexity often means that we cannot “solve” problems outright. Sometimes we can only make things incrementally better. But this should not be a reason for complacency. Instead, it challenges us to co-create solutions that move beyond technical fixes, combining policy, business models and everyday practices to make those incremental steps add up to deeper change.

People at the center

If one theme stood out, it was the role of people and communities, all residents, regardless of background or status. These systems exist to serve the public, funded by tax dollars. Yet without collective participation, even the most advanced infrastructure cannot deliver its full promise. Everyday decisions about what we buy, flush, recycle or discard can make or break the system.

But households cannot carry this responsibility alone. Private sector involvement will also be critical: businesses generate large volumes of waste, shape consumer choices and often lead in innovation. Their stronger presence in Stamford’s strategies could make a meaningful difference.

Beyond the classroom

For us as students, this visit was more than a field trip. It was a hands-on opportunity to question practices, weigh tradeoffs and imagine alternatives. As future policymakers, managers, funders, entrepreneurs or community advocates, our responsibility is not just to admire the systems in place but to interrogate their adequacy and dream of better ones.

The pipes and bins of today reflect collective choices, tradeoffs and values. Are we ready to push those choices beyond incremental fixes toward truly resilient, fair and circular systems?

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Maya Lugo, assistant director of the MPA-Environmental Science and Policy program, and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory research professor Beizhan Yan for organizing this visit as part of the Hydrology course. Special thanks to Dan Colleluori, director of recycling and sanitation; Marylee Santoro, Stamford WPCA Laboratory; and the staff at Stamford’s facilities for their hospitality and valuable insights. We also thank the students for their active participation, which enriched the discussion, and Sara Haris, MPA-ESP program liaison for her contributions to this post.

Views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Columbia Climate School, Earth Institute or Columbia University.

Source link

Guest news.climate.columbia.edu