The optimal design of monetary policy is a challenging task for central banks who always seek the ultimate objective of price stabilization (

Sliman, 2008;

Sghaier & Abida, 2013;

Hammami, 2016;

Turki & Lajnaf, 2024). Tunisia, like other countries, has known evolving monetary policy conduct stages following special events, such as the global financial crisis. The most dramatic episode is the one following the transition period, known as the 2011 revolution (

Guizani, 2015). The economic situation has been marked by a worsening of the current account and budget deficits, an increase in the unemployment rate, and an economic recession with a fall in GDP (

Chtourou & Hammami, 2014). Price stability remains the main objective of the monetary policy, but there is no explicit nominal anchor. The Central Bank of Tunisia (CBT) has taken steps toward a transition to inflation targeting without real success (

Zouhair & Younes, 2009;

Kadria & Ben Aissa, 2014;

End et al., 2020;

E. Trabelsi & Ben Khaled, 2023). Following the fall of the Ben Ali regime, CBT applied an accommodative monetary policy. In 2012, monetary policy tightened with an increase in key interest rates. In addition to the depreciation of the dinar, inflation was fueled by the rise in oil prices and wage increases. There was also a mismatch between supply and demand for goods and services. Banks granted credit to potentially insolvent customers, increasing non-performing loans (

Charfi, 2016). The situation seemed not to be the best with the arrival of COVID-19, plunging the economy back into recession and further uncertainty (

Mansour & Ben Salem, 2020). The spread of the pandemic and the need for short-, medium-, and long-term visibility suggest that viewers feared the worst, either a surge in expansion versus negative growth or a circumstance of stagflation with devastating financial and social consequences. Pandemics, crises, and political instability are perturbing events that generate global uncertainty (

Gupta & Jooste, 2018). In this regard,

Cascaldi-Garcia and Galvao (

2021) show that there has been a growing emphasis among scholars, decision-makers, and economic agents on the impact of risk and uncertainty on financial markets and economic expectations.

It is widely admitted that uncertainty shocks can drive aggregate fluctuations and explain monetary policy transmission mechanisms in modern business cycle research (

Bloom, 2009;

Jurado et al., 2015;

Basu & Bundick, 2017;

Fernández-Villaverde & Guerrón-Quintana, 2020;

Gupta et al., 2020;

Cho et al., 2021;

Bianchi et al., 2023), but the related measures are expansive and categorized (

Caldara et al., 2016;

Kozeniauskas et al., 2018;

Cascaldi-Garcia & Galvao, 2021). We focus on global shocks related to economic, financial, pandemic, and oil price uncertainties. We depart from the view that global and spillover shocks have a larger impact on monetary policy and economic output than local shocks (e.g.,

Bloom, 2009;

Colombo, 2013;

Carrière-Swallow & Céspedes, 2013;

Handley, 2014;

Handley & Limao, 2015;

Jones & Olson, 2015;

Carriero et al., 2015;

Cheng, 2017;

Azad, 2022). Using a novel Bayesian VAR with time-varying coefficients, we disentangle the response of the Tunisian monetary policy to multiple uncertainty shocks. As

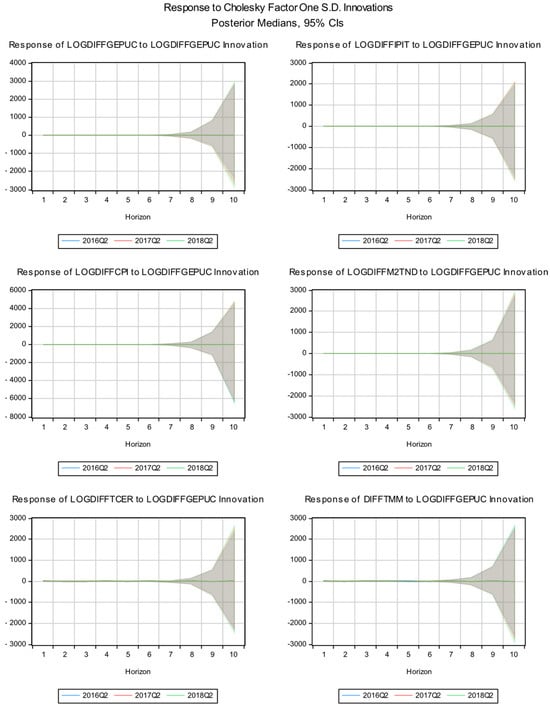

Geraci and Gnabo (

2018) put it, we create a statistical framework based on the market that models the dynamic nature of connections between financial institutions using Bayesian estimation of time-varying parameter vector autoregressions (TVP-VARs). Unlike the classical approach, which favors abrupt, frequently unjustified changes in interconnectedness, the framework permits connections to evolve gradually over time. The approach enables us to reconstruct a dynamic network of directed spillover and global effects. As

Fischer et al. (

2023) claimed, the core of our estimation technique is the specification of appropriate shrinkage priors that allow us to reduce coefficients toward zero concerning effect modifiers that are not important. Since the TVP-VARs depend linearly on the action modifiers, these priorities allow combinations of multiple motion laws and can endogenously determine the correct motion law for the parameters. The Bayesian TVC VAR maintains smooth coefficient changes, and its assumptions may be relevant to real-world economics. One can think of Bayesian TVC Structural VAR as described in

Primiceri (

2005, p. 10). However, the author claims that the flexibility of such a model has some weaknesses. The main one is the “

lack of strong restrictions able to isolate the sources of uncertainty” in the context of monetary policy. Another flexible solution is to rely on local projections (LPs).

Jordà and Taylor (

2024, p. 1) stated that “

Local projections (or LPs) are a sequence of regressions where the outcome, dated at increasingly distant horizons, is regressed on the intervention (directly, if randomly assigned; or perhaps instrumented, if not), conditional on a set of controls that include lags of both the outcome and the intervention, as well as other exogenous or predetermined variables”. Our results indicate that different uncertainty measures explain a statistically significant portion of macroeconomic fluctuations, causing a decline in industrial production and a rise in both the money market rate and consumer price index. Our approach is inspired by

Dery and Serletis (

2021a,

2021b). We differ from their contributions in three main aspects: We analyze a wide range of uncertainty shocks, including real and monetary policy shocks, surpassing the previous literature that often focused on only one aspect of local uncertainty. We assess the forecasting ability of uncertainty shock measures for real economic activity and monetary policy, identifying which measure has predictive power. We use

Toda and Yamamoto’s (

1995) Granger causality test to evaluate the relationship between uncertainty measures and industrial production, the consumer price index, monetary aggregates, the real effective exchange rate, and the money market rate. Third, while risk can be a potentially informative tool in explaining Tunisian monetary policy, we discard the related measures as this goes beyond the scope of the paper and is left for future investigation. Our paper also takes an intriguing step to highlight specific mechanisms that drive the impact of uncertainty on the real economy and prices by calling it the irreversibility theory. This theory suggests that firms often delay investment and hiring during uncertain times. There are two main ways in which uncertainty affects firms. First, the real option, given the irreversibility of the investment, shows the importance of waiting and being flexible when making investment decisions in response to uncertainty (

Henry, 1974;

Bernanke, 1983;

Brennan & Schwartz, 1985;

McDonald & Siegel, 1986;

Bertola & Caballero, 1994;

Caballero & Pindyck, 1996). Consumption patterns are also impacted by uncertainty, especially for durable goods. During high-income uncertainty, consumers may put off making large purchases like homes or cars. Postponing consumption is more difficult for nondurable goods.

Bloom (

2014) argued that this hesitancy expands the real options framework from investment to consumption behavior. In addition to decreasing hiring, investment, and consumption, increased uncertainty makes people less receptive to economic stimuli like tax breaks or changes in interest rates. Businesses and consumers behave more cautiously during uncertain times, reducing the impact of countercyclical policies. Thus, economic stabilization initiatives might need to be more vigorous during these periods. The dynamics of productivity are also disturbed by high uncertainty. Resource reallocation, a major factor in overall productivity growth, is stalled when productive firms are less likely to expand and less productive ones contract more slowly.

Hamilton (

2003) highlighted how uncertainty affects a consumer’s decision by showing several examples (see

Bashar et al., 2013). Second, during periods of uncertainty, higher risk premiums increase the amount of money to compensate borrowers for losses due to increased uncertainty (

Bhatia & Pratap, 2024).

Bloom (

2014) provided a thorough explanation for this fact. Investors seek compensation for bearing additional risk, and increased uncertainty boosts risk premiums, which raises the cost of financing. Moreover, increasing uncertainty heightens the chance of default by enlarging the possibility of extreme negative outcomes. This raises the total expenses of filing for bankruptcy and results in higher default premiums (see

Arellano et al., 2010;

Christiano et al., 2014;

Gilchrist et al., 2014). In models where customers have negative views about future events, uncertainty also affects confidence (e.g.,

Hansen et al., 1999;

Ilut & Schneider, 2014). Agents are unable to assign probabilities to future events due to ambiguity. Rather, they concentrate on the worst-case scenario, a behavior referred to as “ambiguity aversion.” Pessimism increases when uncertainty expands the range of possible outcomes, which leads to a decrease in hiring and investment. According to

Bansal and Yaron (

2004), increased uncertainty also promotes precautionary saving, which lowers consumer expenditure. Growing uncertainty can have serious repercussions for smaller, more open economies (see

Fernández-Villaverde et al., 2011).

The irreversibility theory and precautionary behavior have been examined from an empirical lens.

Yoon and Ratti (

2011) demonstrated that heightened energy price uncertainty causes US manufacturing businesses to be cautious, limiting the responsiveness of investment spending to sales growth.

Bashar et al. (

2013) argued that an increase in oil price uncertainty may hurt the economy via the demand channel. Evidence of partial irreversibility is when monetary policy effectiveness is limited.

Aastveit et al. (

2017) demonstrated how Fed policy has less of an impact on actual economic variables like investment and consumption when there is a high degree of general policy uncertainty. Similarly,

Castelnuovo and Pellegrino (

2018) provided findings from an estimated dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model and a nonlinear vector autoregression (VAR) that bolster the idea that uncertainty reduces the impact of monetary policy.

Andrade et al. (

2019) investigated forward guidance in the context of market participants’ diverse beliefs. Their findings showed that unclear policy signals can lessen the efficacy of directives like forward guidance in a New Keynesian model of monetary policy.

Tillmann (

2020) further argued that policy effectiveness is diminished by monetary policy uncertainty generally, not only by ambiguity surrounding forward guidance.

When faced with high uncertainty, agents adopt more strategic plans, which leads to reduced long-term investments. In our context, this implies investigating the effectiveness of the money market rate as a monetary policy instrument of CBT during high uncertainty times in a VECM where the interest rate interacts with uncertainty variables. Suppose the interest rate does not significantly impact the relationship between uncertainty indices and the real economy and prices. In that case, it indicates that the interest rate is a less influential tool, leading economic agents to adopt a “wait and see” (precautionary) approach. This investigation enhances the uniqueness of our research. Our contribution seeks to address a significant research gap in the Tunisian context.

Source link

Emna Trabelsi www.mdpi.com