Cities sit unmoving on the landscape — a sprawling collection of roads, sidewalks, and buildings designed to last for generations. But across the United States, urban areas are silently shifting: The land beneath them is sinking, a process known as subsidence, largely because people are using too much groundwater and aquifers are collapsing. The sheer weight of a metropolis, too, compacts the underlying soil.

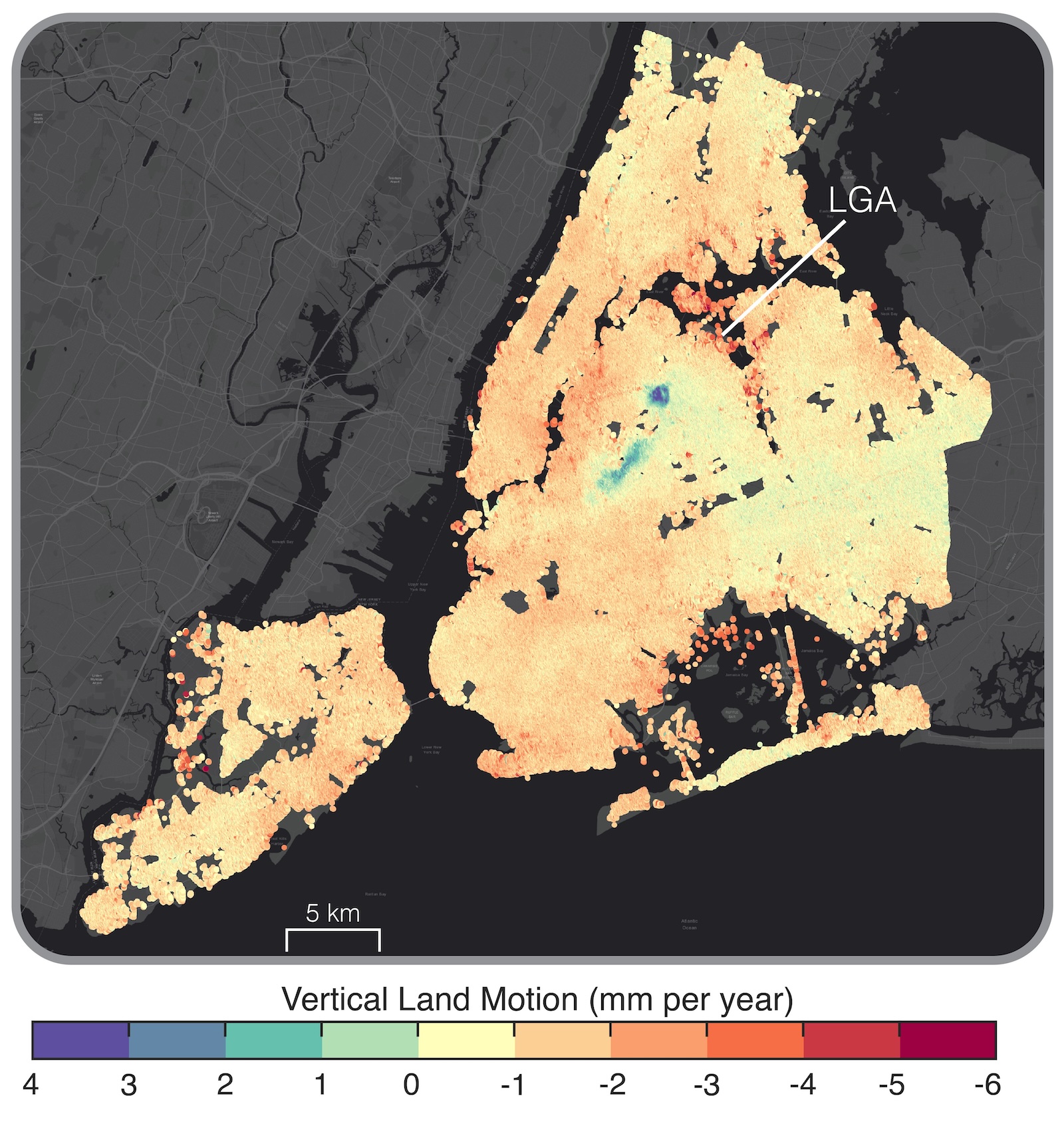

A new study published on Thursday in the journal Nature Cities mapped the scale of this slow-motion crisis across the country. Researchers used satellites to measure how the elevation has been changing in America’s 28 most populous cities — including New York, Dallas, and Seattle — and found that in every one of them, at least 20 percent of the urban area is sinking. In 25 cities, two-thirds or more of the area is subsiding, with rates up to 0.4 of an inch each year. (In the maps below, red indicates areas where subsidence is fastest.)

Groundwater withdrawal was responsible for 80 percent of total subsidence in the cities. As urban areas grow — and as climate change exacerbates droughts, especially in the American West — their people and industries demand more water. Overall, the study found that across the 28 cities, nearly 7,000 square miles of land is subsiding, threatening 29,000 buildings and potentially affecting 34 million people. Hotspots include Los Angeles, Las Vegas, San Francisco, and Washington D.C. “Cities where we have denser population and buildings, we have faster rate of land subsidence, and higher risk of damage,” said Manoochehr Shirzaei, an environmental security expert at Virginia Tech and a coauthor of the paper.

Ohenhen, et al., Nature Cities

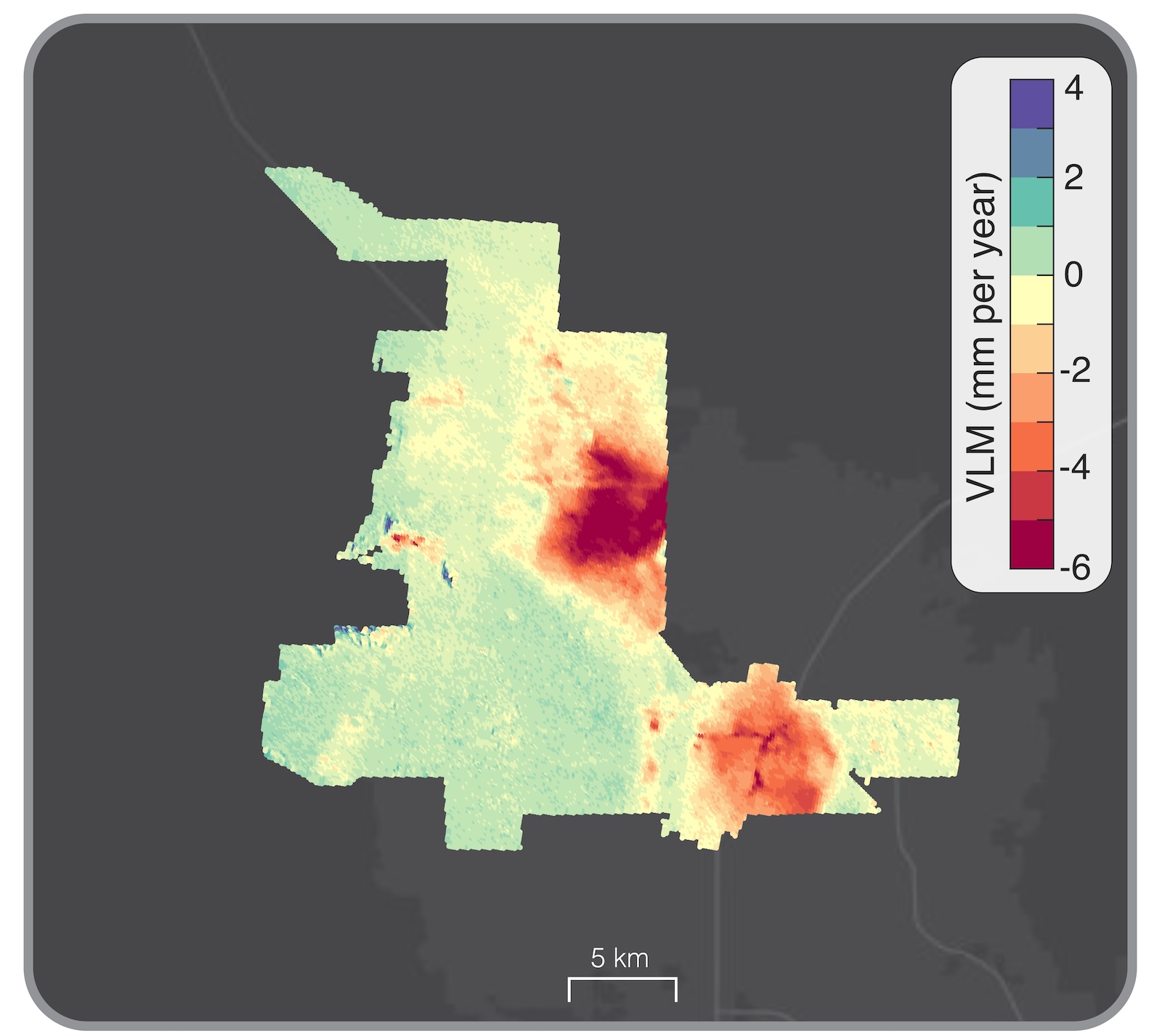

The country’s fastest-sinking metropolis, Houston, has 40 percent of its area dropping more than a fifth of an inch annually, with another 12 percent of its land subsiding at twice that rate. Parts of the city have already sunk by several feet, the result of decades of people pumping out too much groundwater and too much fossil fuel. Houston already struggles with flooding from hurricanes and rainstorms made worse by climate change, while subsidence creates depressions for all that water to accumulate.

If an urban area sinks at a uniform rate, it might not be much of an issue, since all the infrastructure would be moving together. But the problem, the researchers find, is “differential subsidence,” where the rates differ on a small scale. If one end of a building sinks a quarter of an inch a year, and the other end sinks a third of an inch, the difference will destabilize the building’s foundation.

Ohenhen, et al., Nature Cities

While subsidence of a fraction of an inch each year might not seem like much, the years start to pile up: In just a decade, a city can end up with 6 inches of lost elevation. Parts of California’s water-stressed agricultural regions have dropped by nearly 30 feet, and some places in Mexico City are sinking 20 inches every year. “Subsidence is a silent problem,” said researcher Darío Solano-Rojas, who studies subsidence at the National Autonomous University of Mexico but wasn’t involved in the new paper. “Now that the situation with water scarcity is growing, then it’s like, OK, we need to do something about the water, and in parallel, we do something about subsidence.”

Roads and airports, which stretch for long distances across the landscape, are also at major risk because there’s lots of room for differential subsidence: The study found that New York City’s LaGuardia Airport is sinking a fifth of an inch a year. More troubling still, Shirzaei’s previous research scrutinized other infrastructure on the East Coast and discovered that all 10 levees his team measured were sinking, leaving 46,000 people and $12 billion in property vulnerable. Shirzaei has also found that coastal cities such as Charleston, South Carolina, and areas around Chesapeake Bay are sinking a fifth of an inch a year while sea levels rise the same amount, effectively doubling the inundation.

Ohenhen, et al., Nature Cities

Until recently, though, cities have lacked the fine-scale data they need to determine which areas are subsiding, and which buildings and roads might be at risk. “This study just really does the work needed to bring that home, by very systematically assessing this throughout the country and really showing how little we’ve done so far to do anything about this problem,” said Roland Burgmann, a geophysicist who studies subsidence at the University of California, Berkeley but wasn’t involved in the research.

The solution to subsidence is to put water back in the ground, what scientists call managed aquifer recharge, which can reinflate the land. Farmers in California are doing this with excess water during the rainy season so they can pump it back up in times of need. “You’re inherently kind of drawing it down, knowing you can build it back up over time, either through rainfall that’s going to naturally infiltrate and recharge, or through managed aquifer recharge,” said Amanda Fencl, director of climate science for the climate and energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, who wasn’t involved in the research.

So where subsidence is due to the mismanagement of groundwater supplies, it’s also a solvable problem. “With land subsidence, in most cases we have plenty of time,” Shirzaei said, “and we have inexpensive solutions.”

Source link

Matt Simon grist.org